FOI data shows extent of VicPD “use of force”

The B.C. government collects “use of force” data from police departments and publishes some of that data online. That data, which shows that VicPD uses a weapon on someone, or threatens to use a weapon on someone, an average of once a day, is incomplete.

Data obtained via FOI shows VicPD officers regularly use other types of force that the department says it doesn’t track, and which aren’t publicly reported, including putting people in “vascular neck restraints” and punching and kicking people, including people in handcuffs.

“Subject Behaviour-Officer Response”

According to B.C.’s policing standards, departments must complete “use of force” reports, known as “Subject Behaviour-Officer Response” reports, whenever they: use a weapon on someone; threaten to use a weapon on someone; put someone in a vascular neck restraint; use “physical control-hard” (e.g. punch or kick someone, or use a “hard takedown”); or, if they injure the person, when they use “physical control-soft” (e.g. “restraining techniques” and “joint locks”).

An excerpt from a completed VicPD use of force report where the officer says they didn’t use specialty munitions or a firearm, but they had a police dog bite someone. They said it was “effective.”

I first asked VicPD how often their officers were using “physical control-hard” and “vascular neck restraints” in October 2021. VicPD said the government already posted this information online, which isn’t true, and the department didn’t “have the capability” to provide the data.

After the Vancouver Police Department released statistics in response to the same request, I sent a follow-up FOI to VicPD. VicPD said they had looked at spreadsheets the province had compiled from their use of force reports, but they couldn’t extract the data.

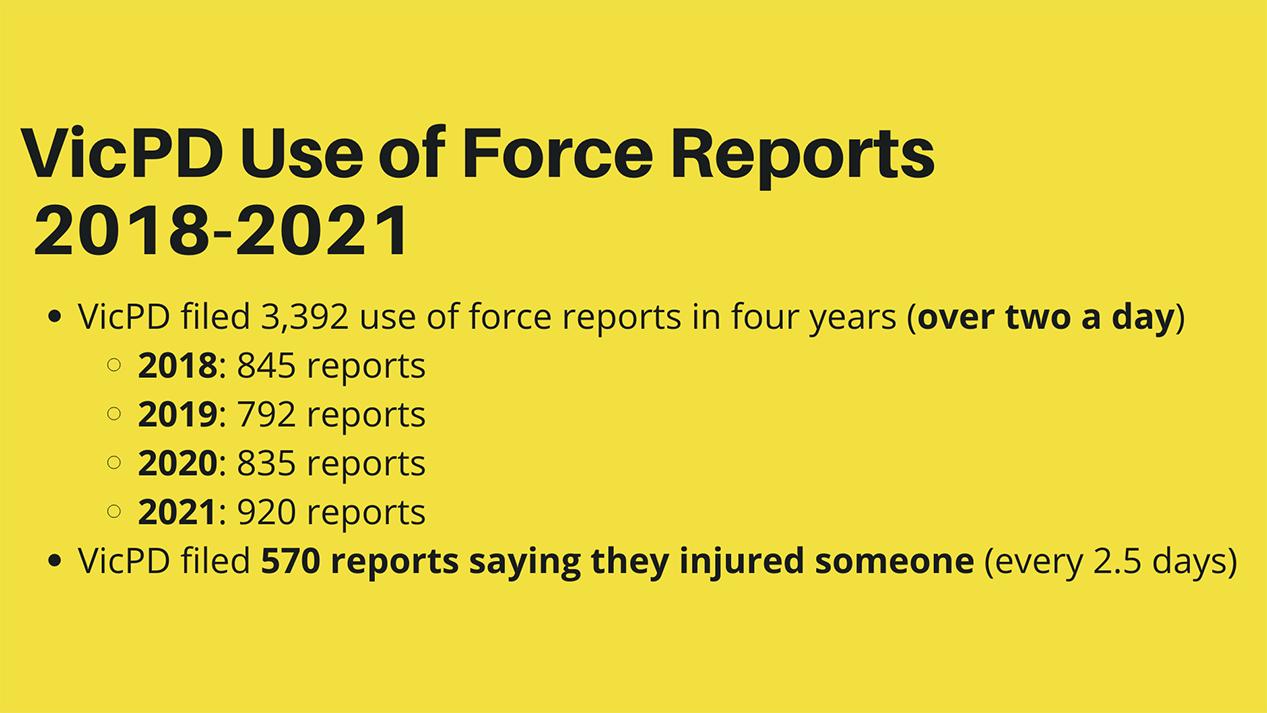

After getting nothing back from VicPD a second time, I asked the province for the spreadsheet VicPD referenced. The following information is taken from that spreadsheet, which includes data from 3,392 VicPD use of force reports filed between 2018 and 2021. That includes 1,174 reports where VicPD said the person was injured, and 570 where VicPD specifically said their use of force had injured the person.

The figures below are based on what officers reported, and likely undercount their actual use of force and responsibility for injuring people. Additionally, while the data VicPD collects on “ethnicity” was not part of the use of force template, all of these statistics should be read with the knowledge that VicPD target Black and Indigenous people.

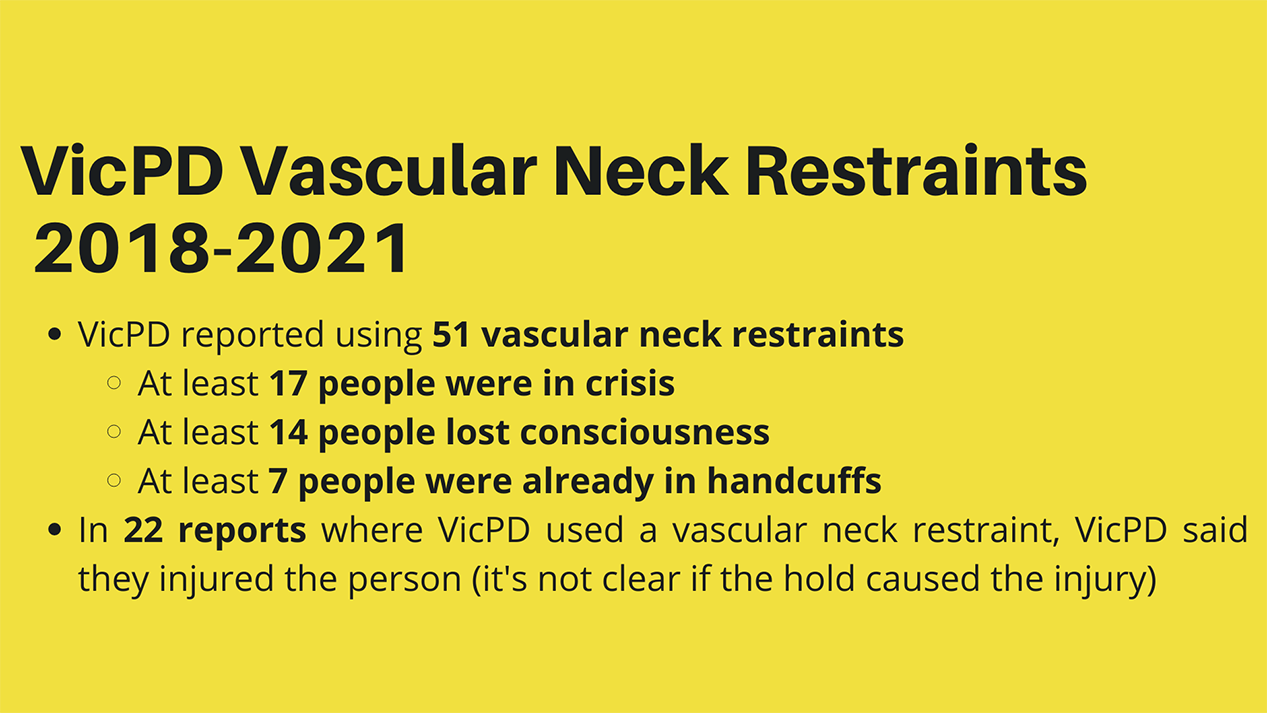

Vascular neck restraints

Data obtained via FOI show that VicPD officers reported using vascular neck restraints 51 times between 2018 and 2021, including five times in VicPD buildings or cells. Vascular neck restraints are designed to cut off blood flow to the brain. The RCMP and other departments argue it is “safe” if used “properly,” but the hold is banned in several jurisdictions. The Dallas Police Department, for example, stopped teaching it in 2004 “after a number of in-custody deaths where the hold might have been a factor.” More recently, the RCMP were ordered to stop using it, but refused.

Illustration of a vascular neck restraint. Image source: David Stroud, Las Vegas Review-Journal, November 27, 2009.

VicPD officers used the hold an average of 13 times a year, and seven times in 2021. By comparison, the RCMP says its officers used the hold 14 times in 2021.

In 14 cases when VicPD used a vascular neck restraint on someone (27% of all vascular neck restraints), they said the person lost consciousness. In 37 cases, 73% of reports where officers said they used the hold, VicPD reported the person was injured. In 22 cases (43%) the officer said they had injured the person, although it is not clear whether it was the neck restraint that caused the injury. In 26 reports where VicPD used the hold, the person was sent to the hospital, including 14 times when the officer said they had injured the person.

VicPD reported that one third of the people they put in vascular neck restraints were in crisis. That figure is based on officers’ perceptions; the actual number of people in crisis who VicPD officers put in the hold may be higher. In three cases when VicPD used the hold, the officer said they did not communicate with the person they used it on, including one person they believed was in crisis.

In 25% of the reports where VicPD said they used a vascular neck restraint, the officer also reported striking the person, an average of three times and up to seven times. In seven cases, VicPD said the person was already in handcuffs when they put them in in the hold, and in one of those cases, an officer seemingly reported that they hit or otherwise struck the person three times after they were in handcuffs.

Because each report is about one officer’s use of force, it is likely other officers used force on some of the same people. The data shows that an average of four officers, and as many as 10, were on site when VicPD used a vascular neck restraint. The province’s data also includes a column that appears to show how many use of force reports were filed by officers from the same department related to the same incident and the same person (“#SBORs for Subject/Incident/Agency”). If that is correct, in 18 cases where a VicPD officer used a vascular neck restraint (35%), multiple VicPD officers — as many as six — filed reports for using force on the same person.

“Physical control-hard”

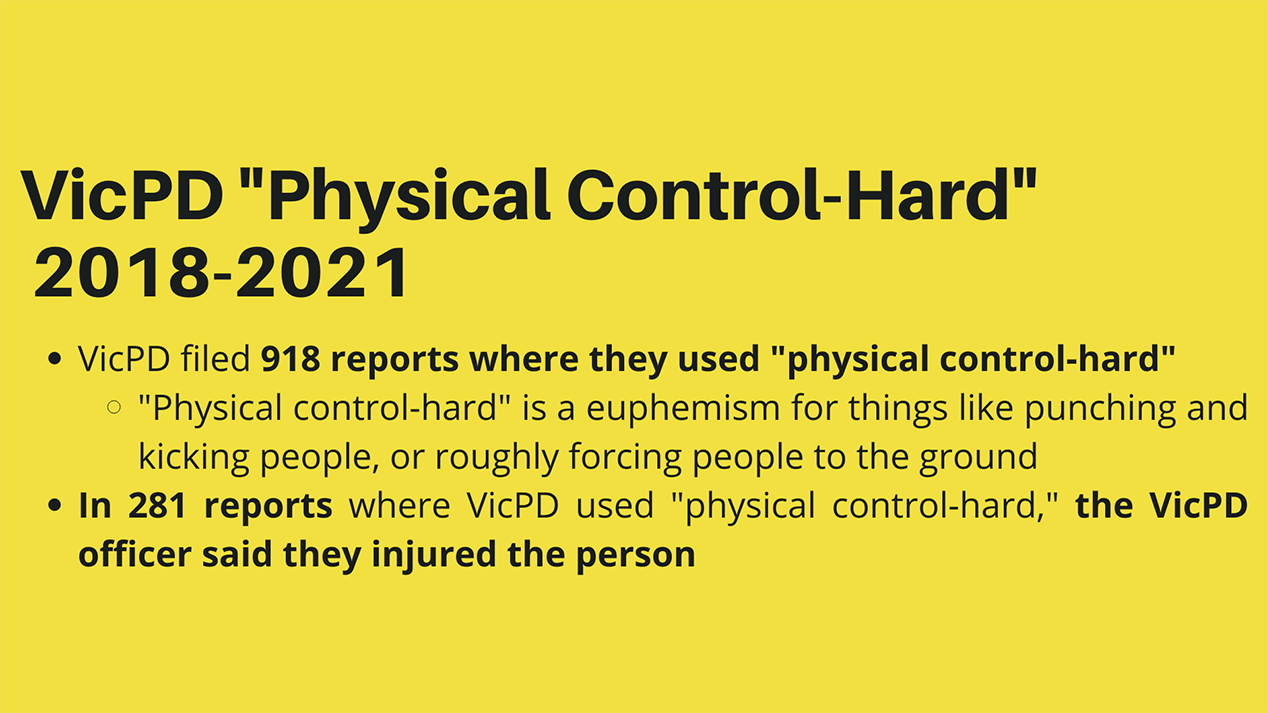

“Physical control-hard” is an official police euphemism for things like punching and kicking people, or roughly throwing people to the ground. A use of force report for the VicPD officer who kicked and kneed people in this 2010 video (see below) might have listed his actions as “physical control-hard.” While the province collects this data, it doesn’t currently publish the information in its police use of force statistics.

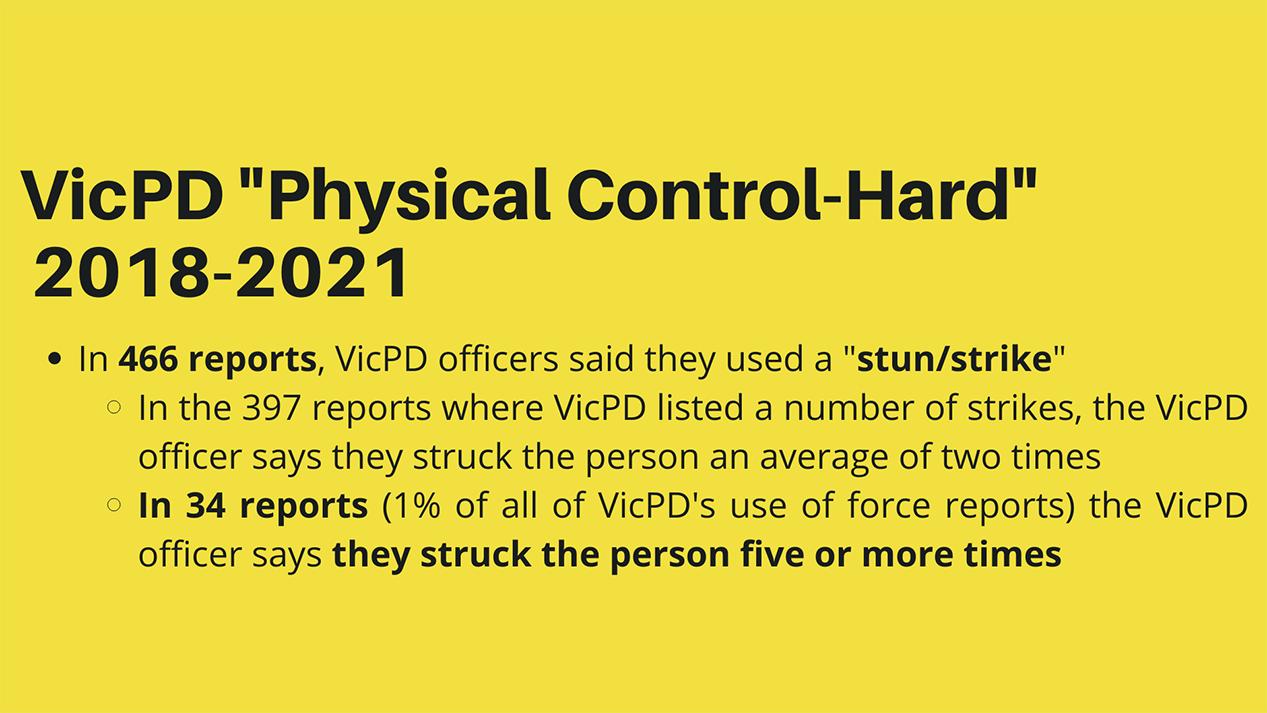

In 918 of VicPD’s use of force reports between 2018 and 2021 (27% of all of VicPD’s use of force reports), the VicPD officer said they used “physical control-hard.” In 466 reports, VicPD officers said they used a “stun/strike,” and in 397 reports (12% of all reports) the officer listed a number of strikes, noting that they had punched, kicked, or otherwise struck the person an average of two times. In 34 of VicPD’s reports (1% of all of VicPD’s use of force reports) the officer said they struck the person five or more times.

In 502 (15%) of VicPD’s use of force reports, they said they used a “hard takedown.” In 97 cases, officers said they used another, unlisted type of “physical control-hard.”

In 281 reports (31% of reports where VicPD reported using “physical control-hard”), VicPD said they injured the person.

Using violence on people in handcuffs

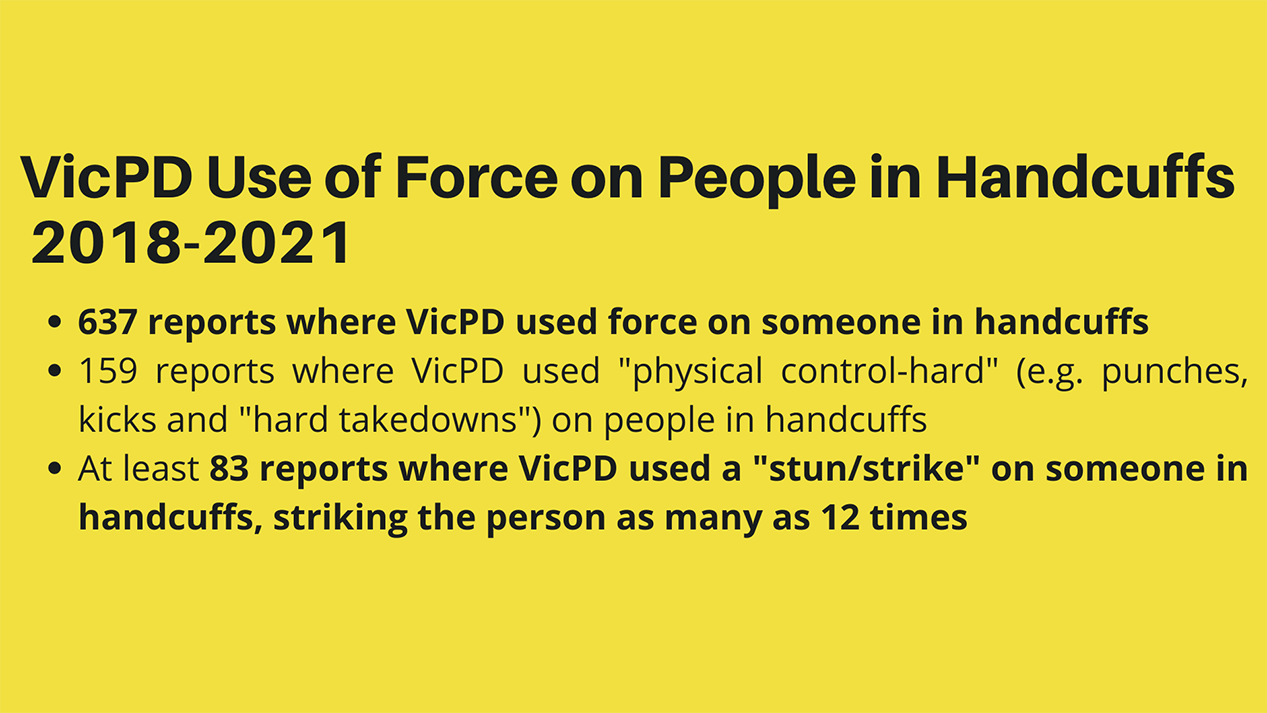

B.C.’s use of force reports ask officers if the “subject [was] handcuffed prior to force response.” Between 2018 and 2021, VicPD filed 637 reports where they said they used force on someone in handcuffs.

VicPD officers filed 159 reports where they said they used “physical control-hard” on someone already in handcuffs, including 51 reports where VicPD officers said the person was in crisis. There were at least 83 reports where VicPD officers said they used a “stun/strike” on someone in handcuffs. In those reports, VicPD officers said they “struck” the person an average of 2 times and as many as 12 times.

Data shows one “use of force” report where the officer says: they struck someone 12 times; they struck the person after they were already handcuffed; they injured the person; and the person was sent to the hospital. “Subject IBPOF” stands for “Subject injured by police officer force.” The officer did not complete the field for whether the person was injured prior to their use of force.

There may be as many as 104 reports where VicPD officers admit to striking someone in handcuffs, but when officers used multiple types of “physical control-hard,” the data does not clarify which type of force they used after they put the person in handcuffs.

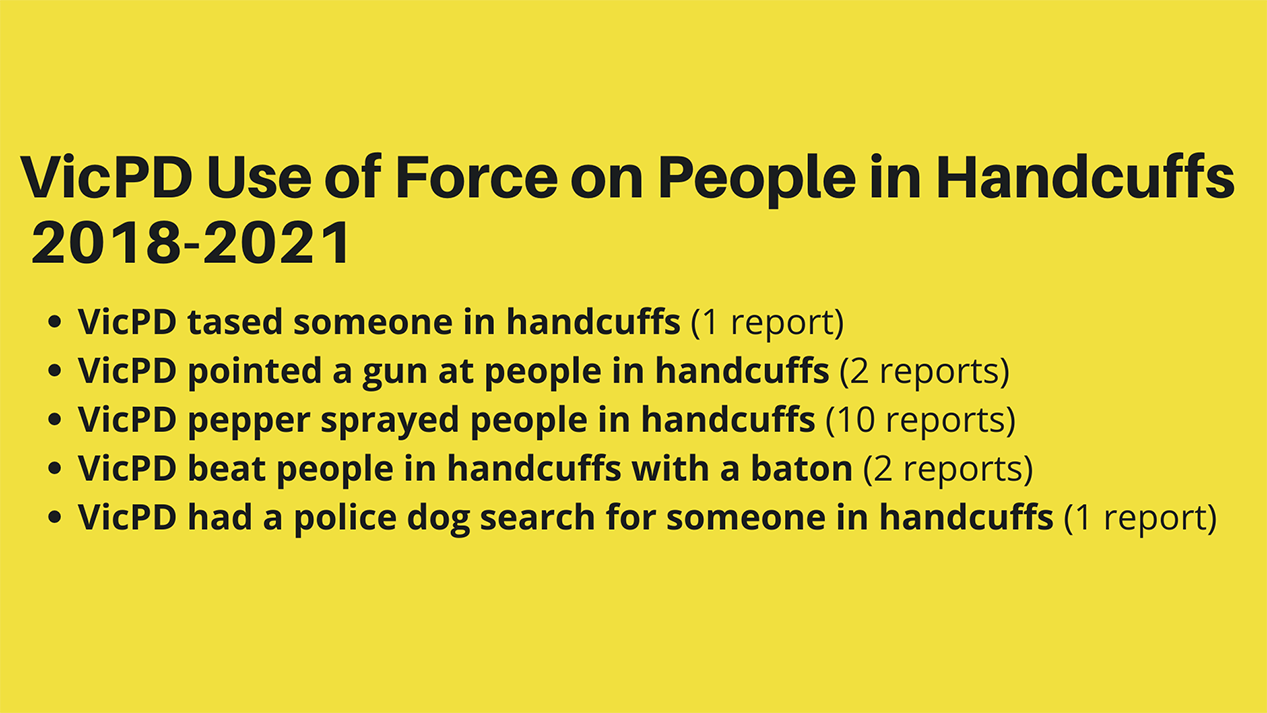

Between 2018 and 2021, VicPD also reported that they:

Tased someone in handcuffs (1 report)

Pointed their gun at people in handcuffs (2 reports)

Pepper sprayed people in handcuffs (10 reports)

Beat people in handcuffs with a baton (2 reports)

Released a police dog to search for a person in handcuffs (1 report)

Used “other” types of force on people in handcuffs (6 reports)

Put people in “escort/come along” holds (at least 149 reports, and up to 325)

Put people in joint locks (at least 86 reports, and up to 217)

Used “pressure points” (at least 23 reports, and up to 95)

Used “Other” types of “physical control-soft” (at least 79 reports, and up to 120)

In 44 reports where VicPD says they only used “physical control-soft,” and that they used it after the person was in handcuffs, the officer said they injured that person.

Police respond to people in crisis with violence

Police violence can happen anytime an officer is present. Data shows VicPD’s use of force reports were filed by jailers, bike cops, patrol officers, the “Emergency Response Team,” the “Late Night Task Force,” and, critically, mental health response units and ACT teams.

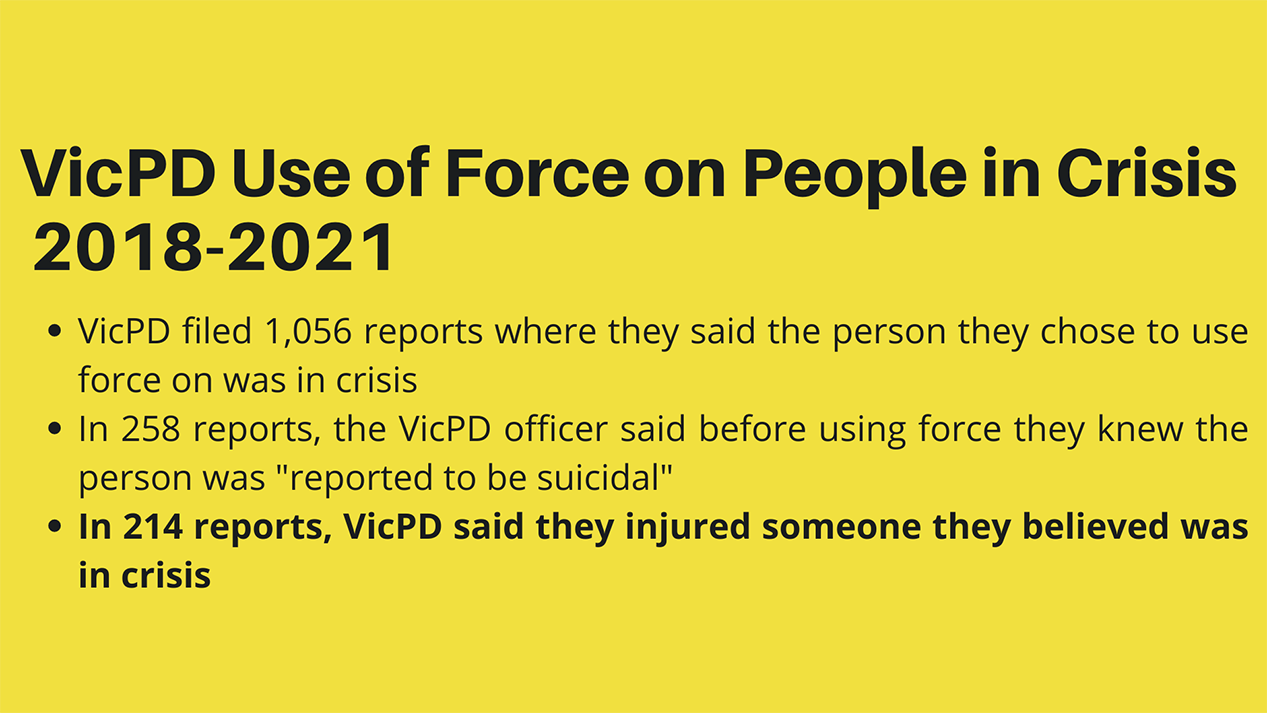

When VicPD officers respond to people in crisis, they regularly use violence. In 1,056 of VicPD’s reports where officers chose to use force between 2018 and 2021 (31% of all reports), the officer said they believed the person was in crisis. In 935 reports, the officer said prior to using force they were aware that the person “suffered from mental health issues.”

In 214 reports, VicPD said they injured the person they believed was in crisis, including 162 people who wound up in hospital.

When Lisa Rauch was in crisis in 2019, VicPD shot and killed her with ARWEN rounds. VicPD filed 49 reports between 2018 and 2021 where they fired an “extended range impact weapon” at people, including 29 reports where VicPD says they fired at people in crisis. VicPD fired ARWEN rounds in 31 reports, beanbag shotguns in 16 reports, and another type of weapon in two reports. In 42 reports VicPD said the person was injured (not necessarily by the ARWEN round or beanbag shotgun), including 27 times where VicPD explicitly said their use of force injured the person.

Photo of a March 2022 VicPD mental health response where at least eight armed officers responded. VicPD shot the man in crisis with an ARWEN round. Background here.

In 258 reports between 2018 and 2021 (8% of all reports), the VicPD officer said prior to using force they were aware that the person was “reported to be suicidal.” After VicPD shot and killed a still-publicly unnamed man on September 12, 2021, the dataset shows that VicPD filed a use of force report noting the man was in distress, had a knife, and was wishing harm upon himself, all of which has been publicly reported. When asked in the same report to indicate whether shooting him had been “effective,” VicPD said “yes.”

Chief Del Manak has derisively asked if “people [are] suggesting that social workers should start responding to current calls where police respond.” Social workers would not have shot and killed that man in September, 2021. Despite VicPD’s efforts to entrench themselves in mental health response, police are not and will never be mental health workers.

The data shows that VicPD files one report a week that says they’ve injured another person in crisis. When VicPD responds to mental health calls in any capacity, it puts that person’s life at risk.

Police violence anytime, anywhere

The phrase “use of force” is a euphemism to mask police violence. That violence is not limited to urgent circumstances or emergencies, and it is subject to little meaningful oversight.

VicPD regularly makes “breach” arrests, which often refer to arresting people for things like missing a court date. People in “breach” may not be able to make those court dates or safely abide by conditions that prevent them accessing parts of downtown Victoria. The data shows that at least 235 of VicPD’s “use of force” reports started with officers enforcing “breaches” or probation conditions. VicPD has called these type of arrests, which the data show can include police violence, “good police work,” saying they “breach people and breach them again.” VicPD will sometimes publicize these arrests online.

At least 36 situations where VicPD escalated to using force were related to people possessing substances. And in 38 reports, the incident that culminated in VicPD choosing to use force was “shoplifting under $5,000.” In 11 of the shoplifting reports, VicPD said they used “physical control-hard”; in three reports, the officer says they struck the person; and in one they used pepper spray. In five cases — all responding to initial allegations of someone shoplifting items worth less than $5,000 — VicPD threatened the person with a handgun. From alleged shoplifting to threatening deadly force.

Police violence marketed as community safety

Publicly released data had already shown that VicPD uses a weapon on someone, or threatens to use a weapon on someone, an average of once a day. It speaks to a lack of accountability that VicPD twice said they would not and could not release the additional information on police violence documented here.

It is in the public interest to know how often VicPD puts people in neck restraints that the RCMP has been ordered to stop, and how often VicPD officers punch, kick and knee people, including people they’ve already put in handcuffs. People should know how often VicPD are violent with people in jail (398 reports for using force in a police building or cells), and how often VicPD puts people in holds that they get to call “soft,” but which still injure people.

With 3,392 use of force reports over 4 years — more than two a day — VicPD is regularly harming people, but details on the vast majority of police violence in Victoria are never made public. The fraction that trickle through are mostly told through police press releases or Independent Investigations Office reports, both of which tell the public and the media that any police violence was in the name of safety, and was the only possible outcome.

Eventually the Independent Investigations Office will issue a report saying that VicPD had to shoot and kill the man who was in crisis on September 12, 2021. And if asked, VicPD will say that sometimes their officers have to beat people they’ve already put in handcuffs. Or point a gun at someone who was accused of shoplifting. If only we knew the circumstances!

Any defence of police violence assumes that police and police violence are inevitable. They are not.

This fall, the Victoria and Esquimalt Police Board will ask for more than $70 million to fund a police force that is regularly violent, including with people in crisis and people they’ve put in handcuffs. VicPD will continue to put people in hospital, and they will continue to kill people in distress. It is a choice to continue to fund that violence.

Download VicPD use of force data, 2018-2021. The spreadsheet includes a worksheet where all data may be filtered; a worksheet with only reports that include vascular neck restraints; and a worksheet with the data as originally released by the province (filtering will not capture all rows on this worksheet).