B.C. police departments disproportionately street check Indigenous and Black people

Over a decade of data obtained from B.C.’s municipal police departments through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests show the departments disproportionately street check Indigenous and Black people.

This isn’t surprising; racism and other discriminatory practices in street checks have been well documented across the country. The complete data set and statistics are available for download at the end of this post.

While these data provide yet another example of the systemic racism that’s at the core of policing in B.C. and Canada, the stats aren’t needed to show that policing in B.C. is racist. In a 2017 Globe and Mail interview, Desmond Cole said the fact that white people need statistics “before they will get up and open their mouths … tells me they are not hearing, and particularly not believing, everyday stories and experiences of Black and Indigenous people.”

In March, 2018, Michael Regis presented a report to the Victoria and Esquimalt Police Board that included stories from Indigenous, Black and Muslim people who were profiled and surveilled by Greater Victoria police departments. Past reports by SOLID in 2015 and VIPIRG in 2012 included similar experiences with the Victoria Police Department (VicPD). The police board only had two questions for Regis, one of which included the observation that “some of those groups don’t even get along amongst themselves.” It’s not clear whether the board actually read Regis’s report, but either way, they weren’t interested in holding the department accountable.

Excerpt from the Michael Regis report, “Policing in Greater Victoria: A Study in Addressing the Gaps in Engaging Greater Victoria's Diverse Communities.” Text says: “Racial and faith profiling. Profiling and over-surveillance were consistent themes within the findings of Muslim, Aboriginal and African-Caribbean groups of this project. They indicated that African-Caribbean residents feel that they are unjustly targeted, stopped, ticketed and maltreated by the [Greater Victoria Police] and are profiled at a greater rate than any other race.”

When the Vancouver Police Department published street check statistics in 2018, Elaine Durocher, Métis grandmother and board member of the Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre, said in a BC Civil Liberties news release, “As Indigenous people and … people of colour living in poverty, we are routinely stopped by the police on every block – from our home, to the food lineup, to our volunteer work – for no reason other than to question and intimidate us.” Black Lives Matter Vancouver situated Vancouver’s street check stats in the context of “numerous other reported instances of anti-Blackness in Vancouver.”

It shouldn’t have surprised anyone paying attention that Vancouver PD’s street check statistics showed that the department disproportionately street checked Indigenous and Black people, and particularly Indigenous women. Officers street check people they consider “suspicious,” and officers and police forces perceive Black and Indigenous people as suspicious because policing is racist.

Nor should it surprise the VicPD police board that 9.9 per cent of people included in VicPD’s street check reports between 2007 and 2017 were Indigenous, and 2.4 per cent were Black, when Indigenous and Black people respectively make up 5 per cent and 1.4 per cent of Victoria and Esquimalt’s population. If they somehow hadn’t heard it before, the board was told by Regis in 2018, at their own meeting, that Greater Victoria police profile and surveil Indigenous and Black people.

Nobody should need stats, graphs and spreadsheets to know policing is racist, and that street checks exist within the context of police discrimination and violence against Indigenous and Black people. But for any police department or board surprised by these numbers, or for anyone looking to undermine them: these stats are absolutely less credible and less important than what people in your communities have been saying for years. B.C.’s municipal police departments uphold systemic racism every day, and not just through their street checks.

Summary of Statistics

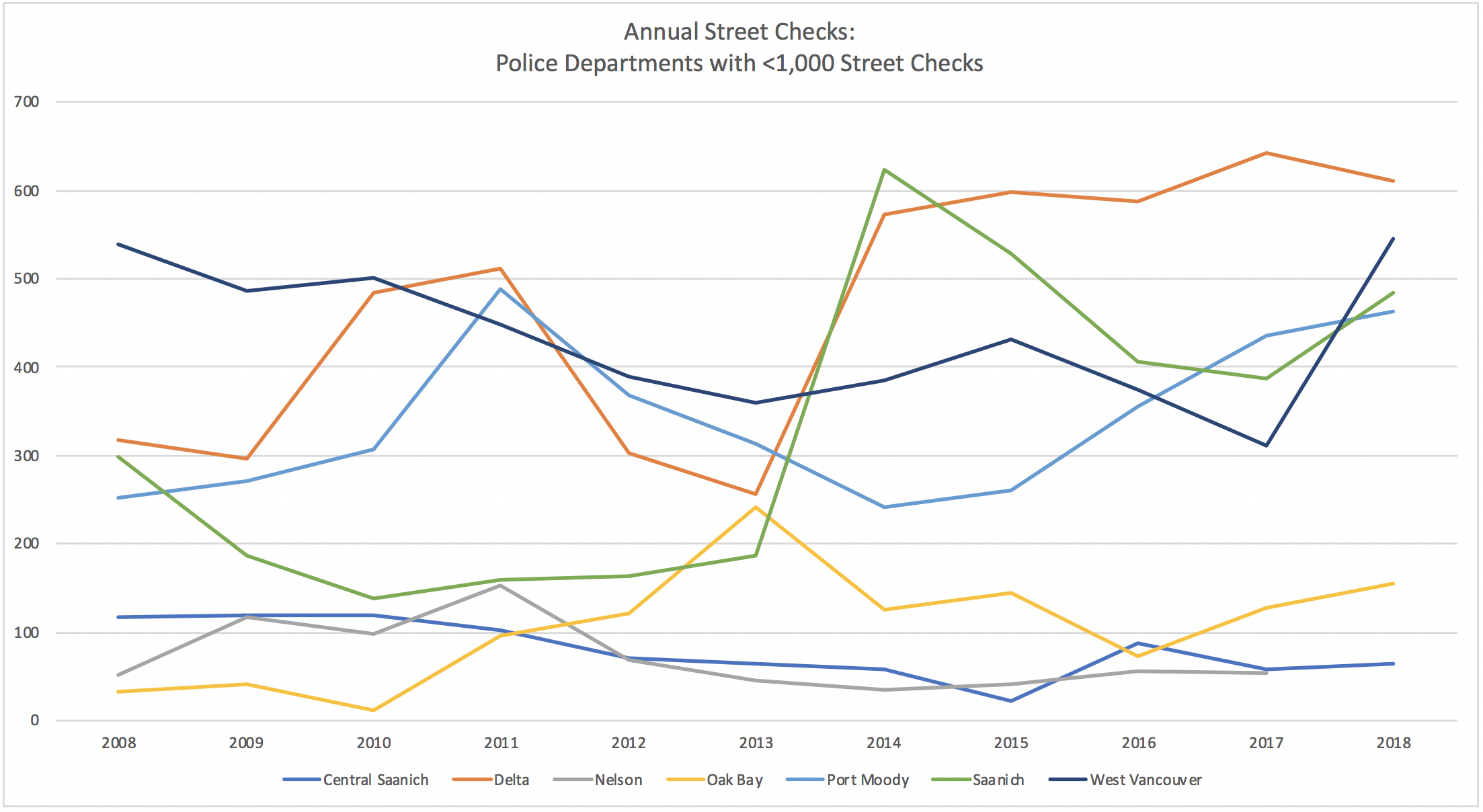

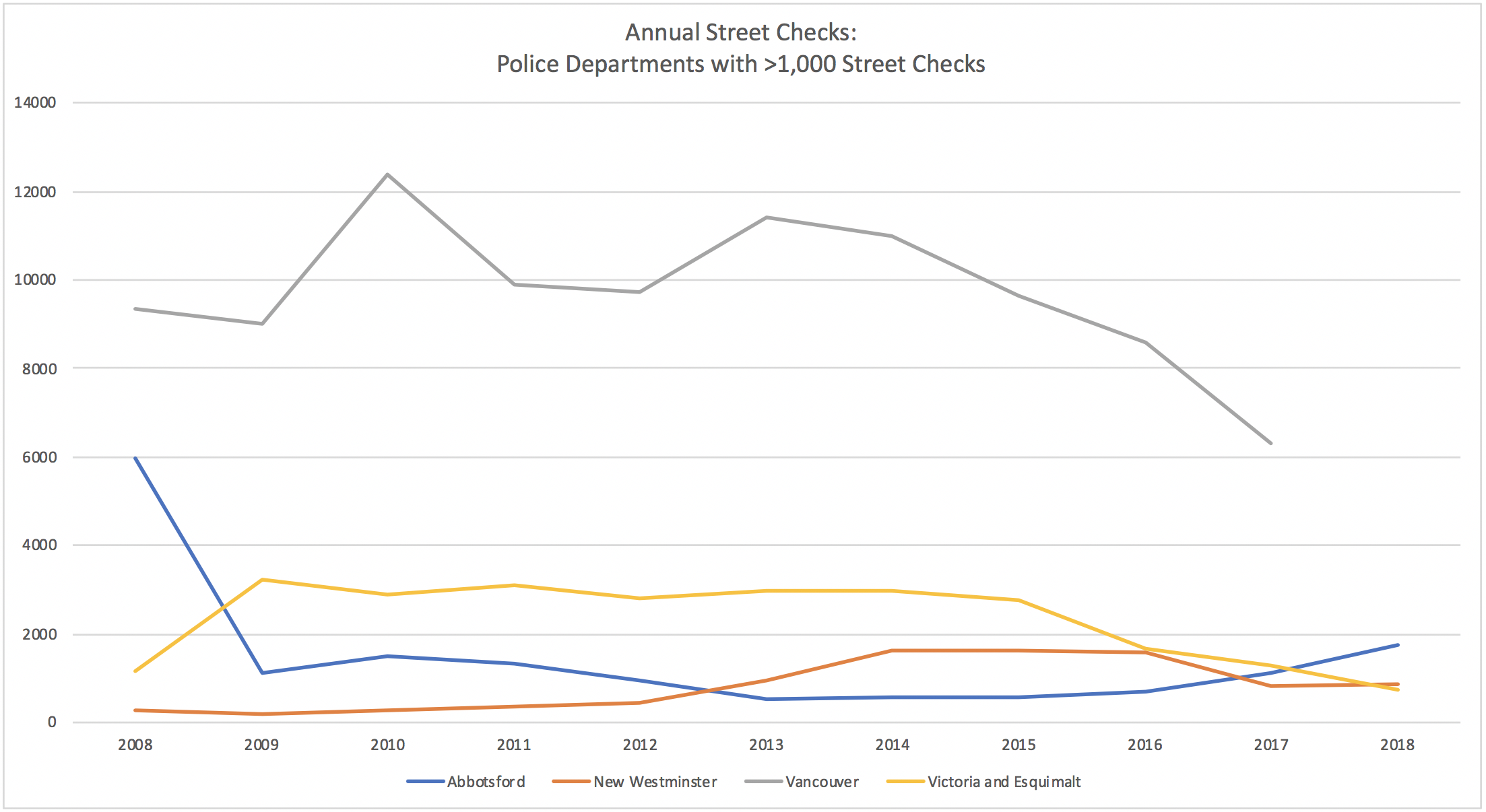

There are 11 municipal police departments in B.C.: Abbotsford, Central Saanich, Delta, Nelson, New Westminster, Oak Bay, Port Moody, Saanich, Vancouver, Victoria and West Vancouver. Policing in other locations is handled by the RCMP.

I requested data from each municipal police department for:

Yearly totals for number of individuals street checked, as well as number of street checks by: sex and ethnicity (2008 – 2018);

Yearly totals for street checks by gender, with that gender information further broken down by ethnicity (2008 – 2018); and

Yearly total street checks, as well as street checks by: type; reason; district; zone; and unit (2008 – 2018).

With some gaps, most departments provided the information requested. Note that the Vancouver PD data is the same as what was published in 2018. Vancouver PD and VicPD provided information up to 2017 due to the timing of those requests, and Nelson PD provided data up to 2017 to match Vancouver’s response. While VicPD initially refused to release any data, that information was obtained after multiple follow-up FOIs.

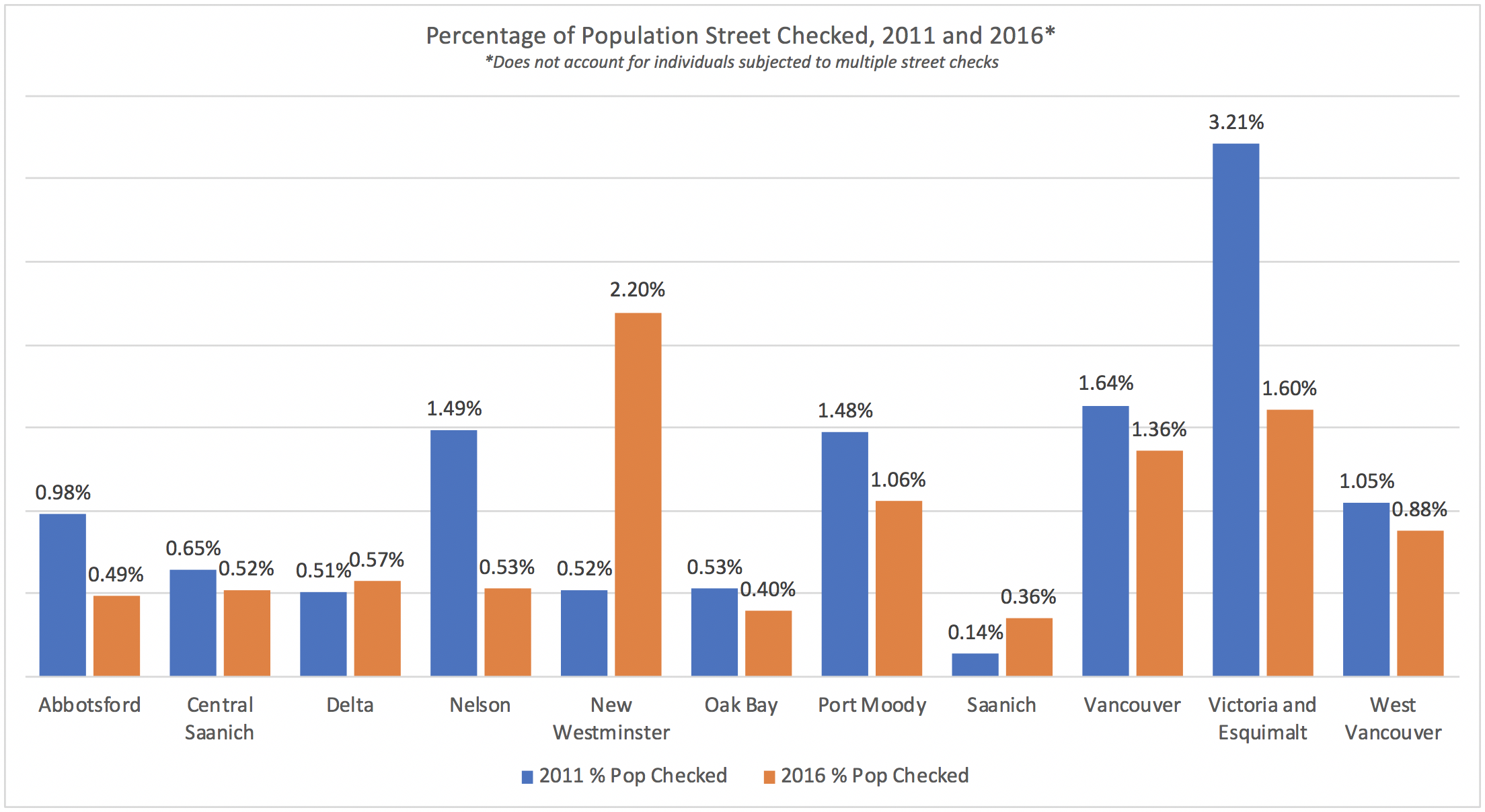

New Westminster reported the most street checks compared to its population. In 2016, New Westminster PD performed 1,559 street checks, or enough for the department to have street checked 2.2% of the population, not accounting for people subjected to multiple street checks. VicPD and Vancouver PD followed with 1.6% and 1.36%, respectively.

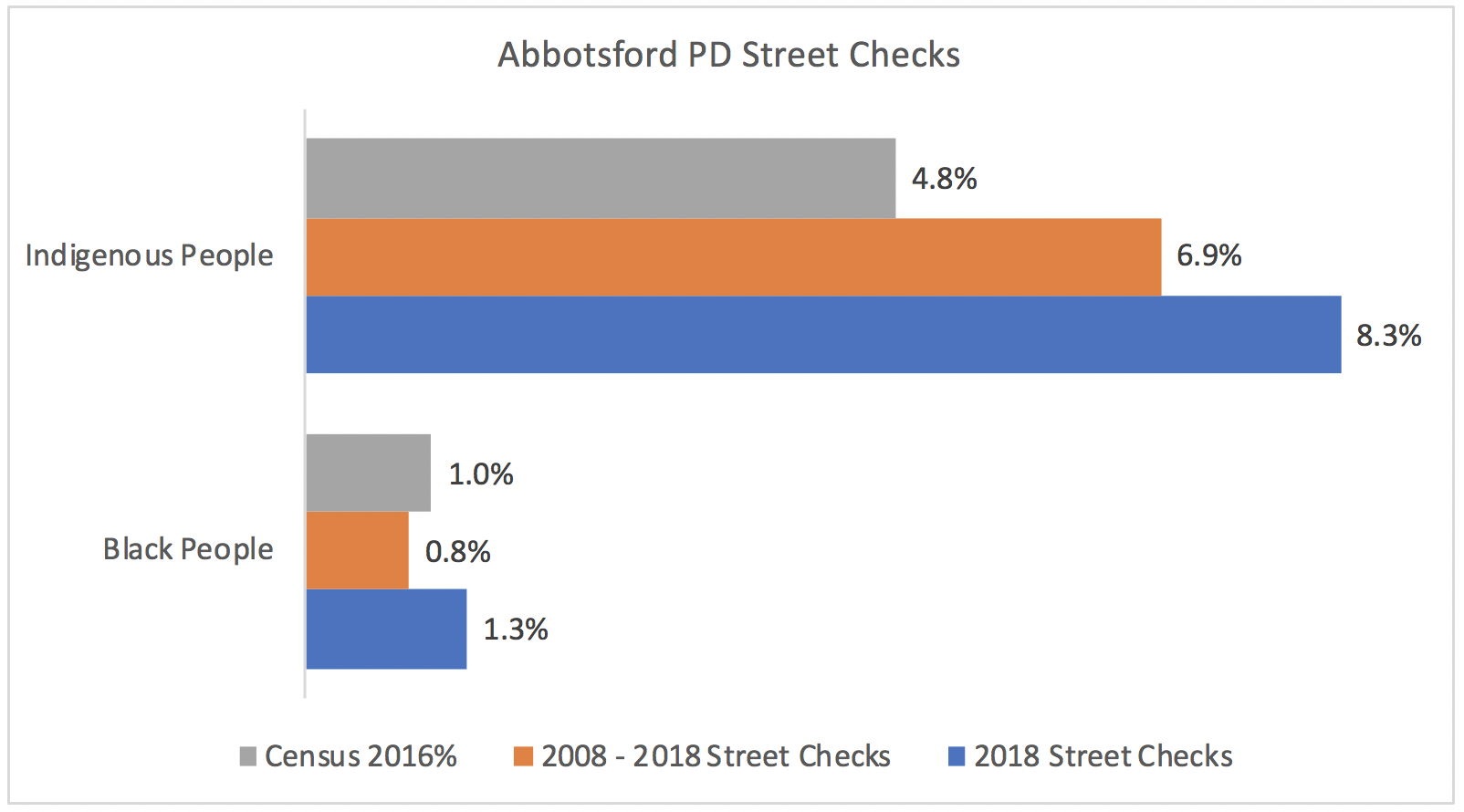

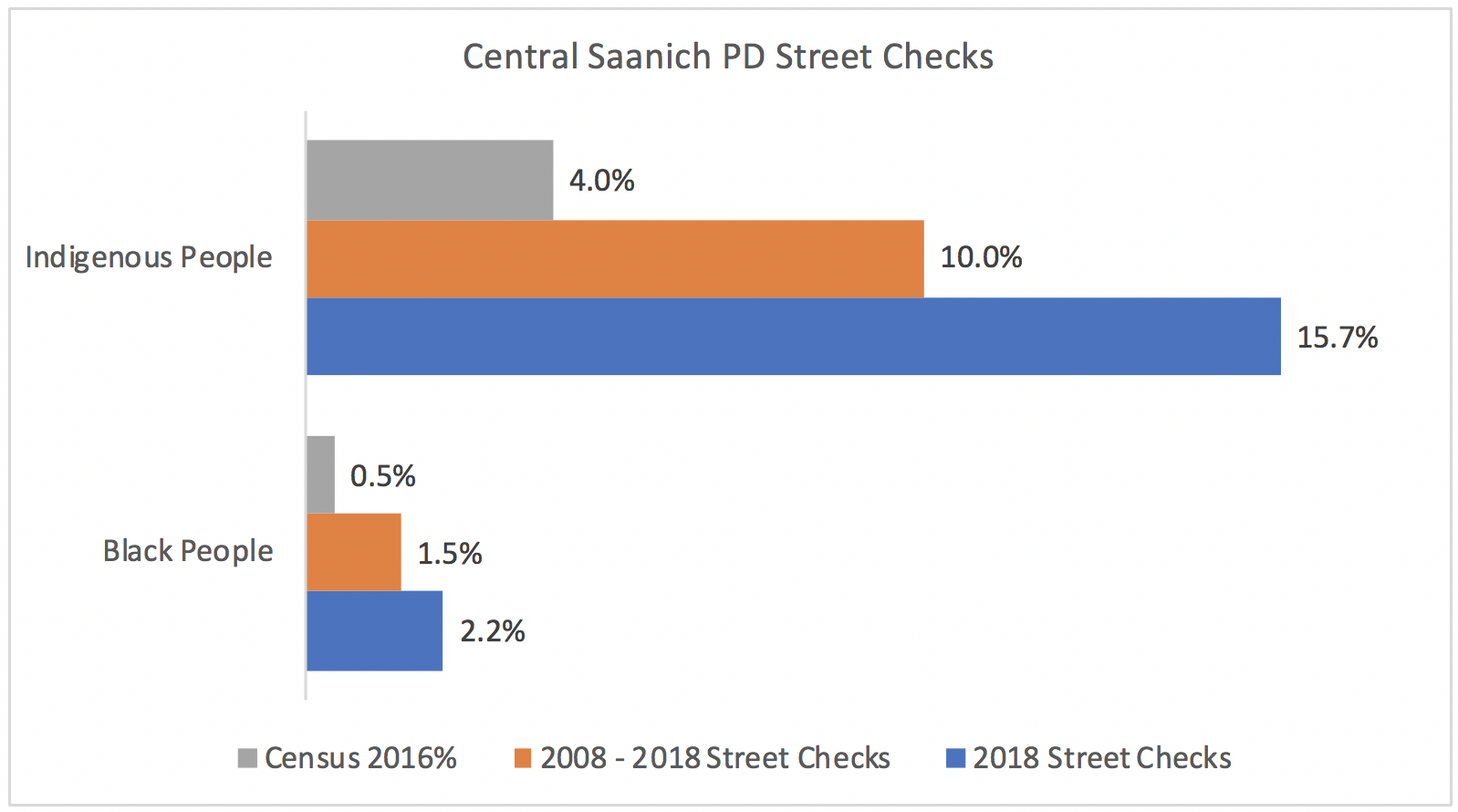

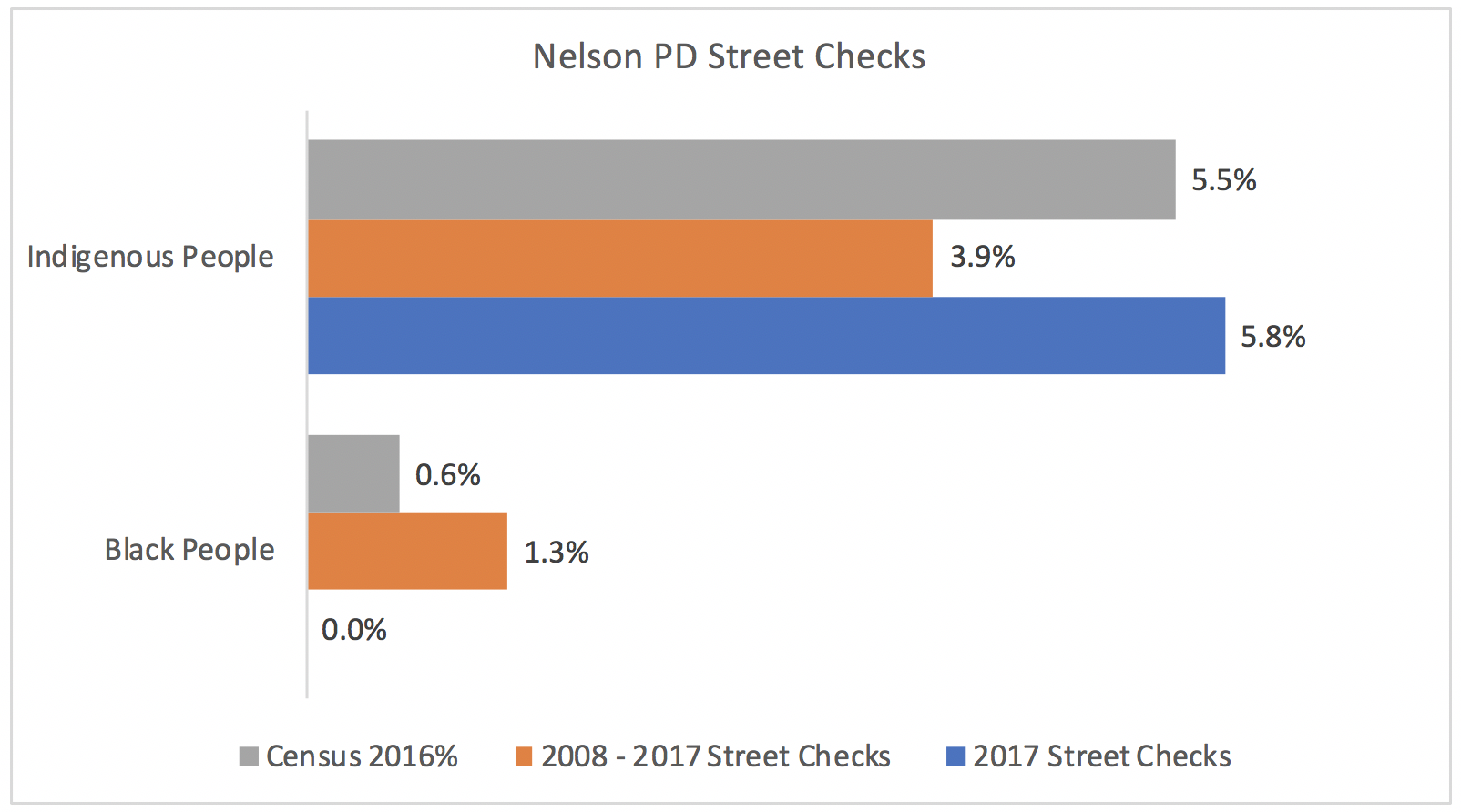

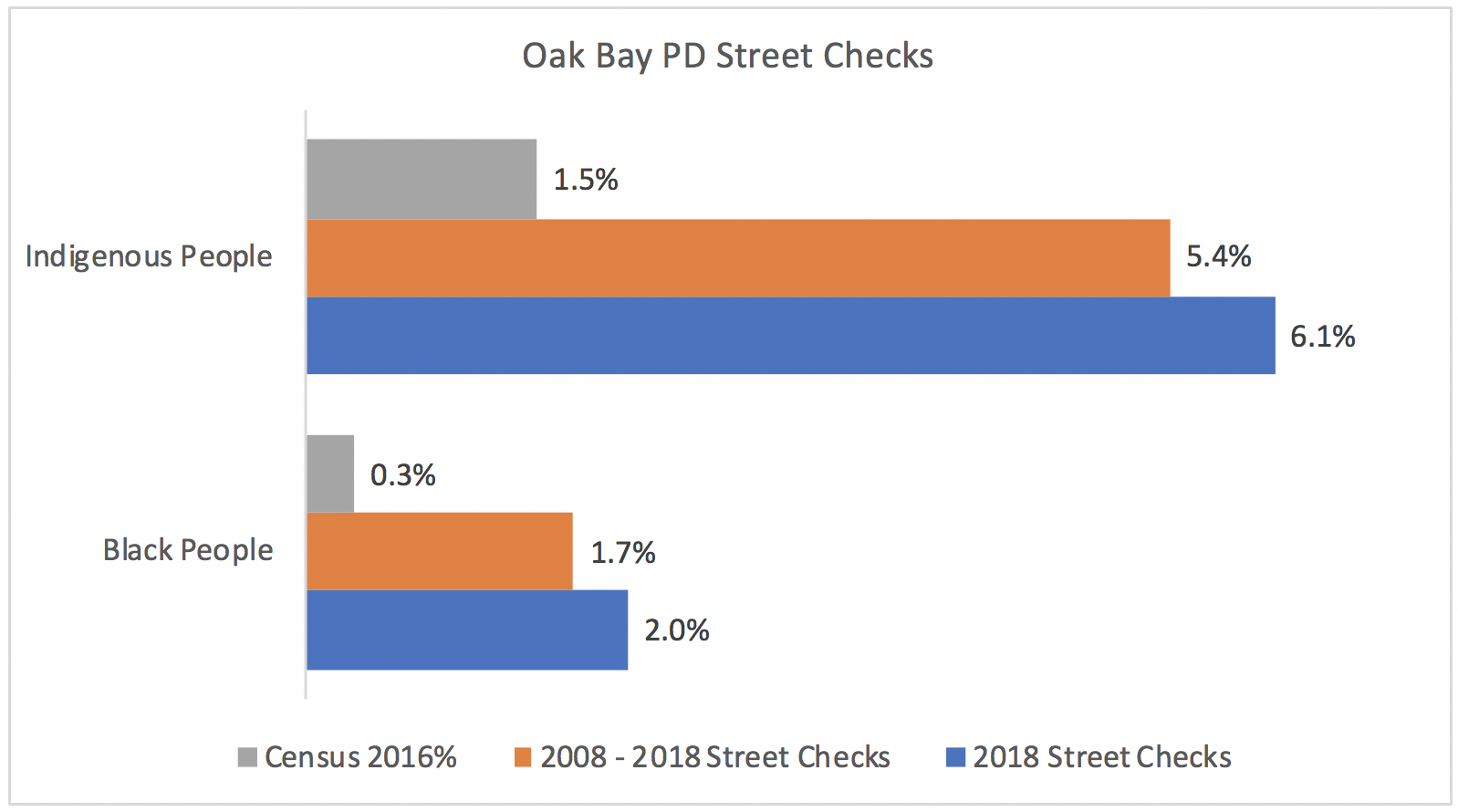

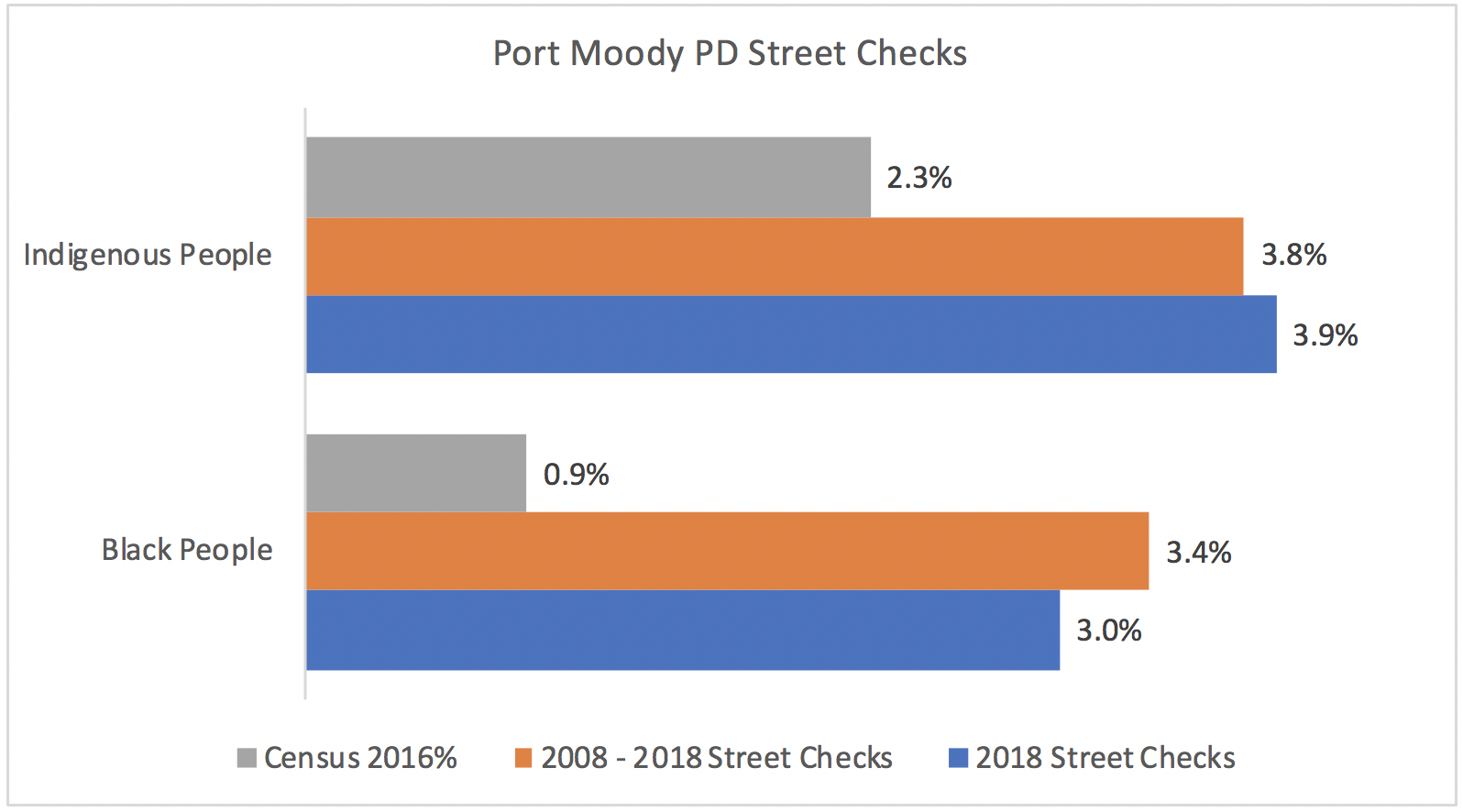

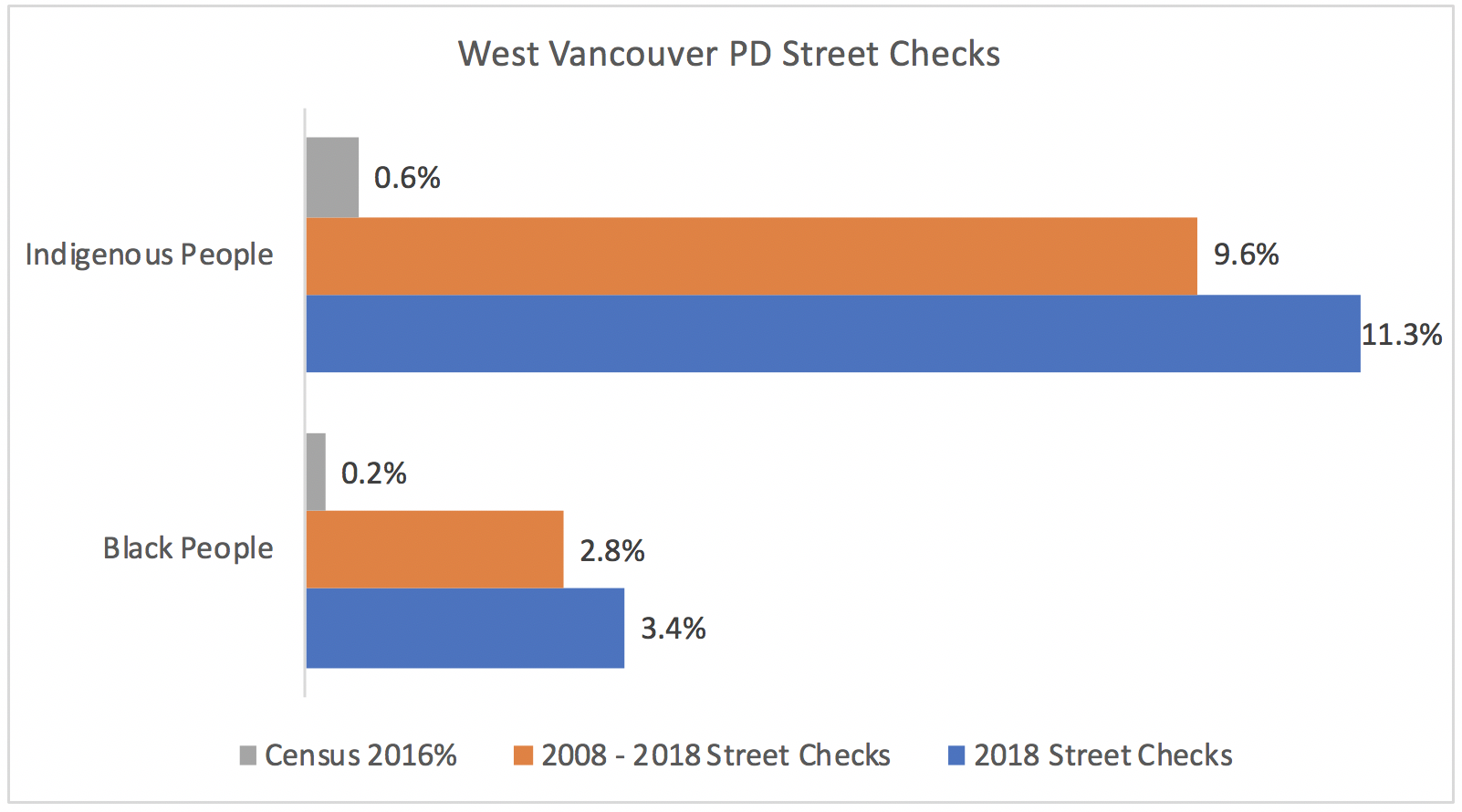

The data police collected on street checks includes “ethnicity” information that shows a consistent pattern of police disproportionately targeting Indigenous and Black people. Indigenous people make up 0.6% of the population in West Vancouver, but accounted for 9.6% of street checks between 2008 and 2018. In New Westminster, Indigenous people are 3.3% of the population but made up 9.3% of the street checks. In Oak Bay, Black people make up 0.3% of the population but 1.7% of the street checks. In West Vancouver, 0.2% of people are Black, while Black people make up 2.8% of the street checks. Numbers for all municipal police departments are below.

Street checks where ethnicity was recorded as “Blank” or “Unknown” were excluded from totals when calculating percentages.

The ethnicity data relies on officers’ perceptions and assumptions, and is sometimes left blank or marked “Unknown.” For Vancouver PD, VicPD and Oak Bay PD, the ethnicity field was left blank for 10.9%, 6.5% and 3.1% of people street checked, respectively; Central Saanich and Delta listed people’s ethnicity as “Unknown” for 6.4% and 2.2% of street checks. Other police departments had blanks ranging from 0% to 1.5%, and “Unknowns” ranging from 0.4% to 1.4%. The reliance on officers’ perceptions as a stand-in for determining identity, as well as the incomplete data, mean that the number of Indigenous and Black people street checked in B.C. is likely underreported.

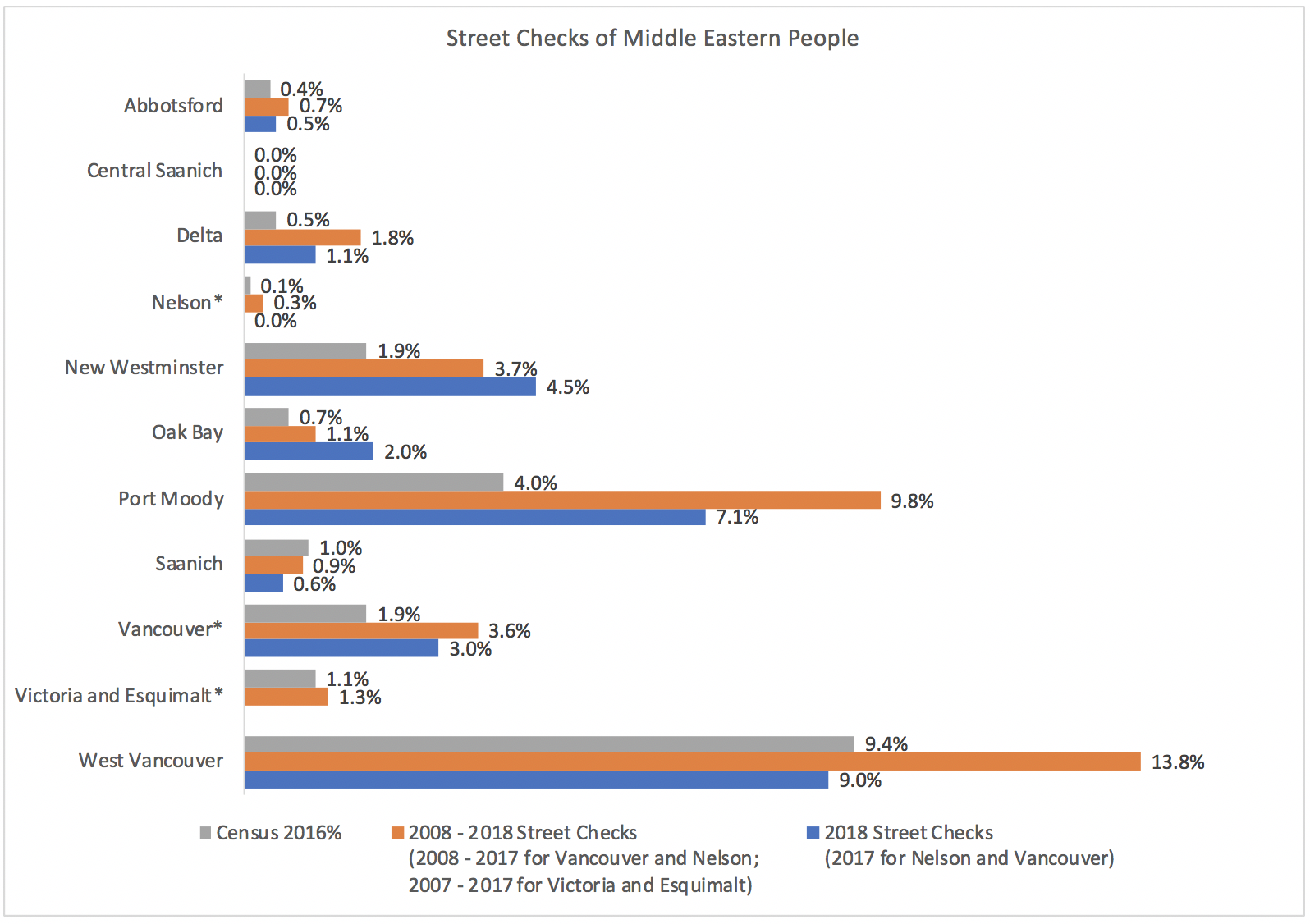

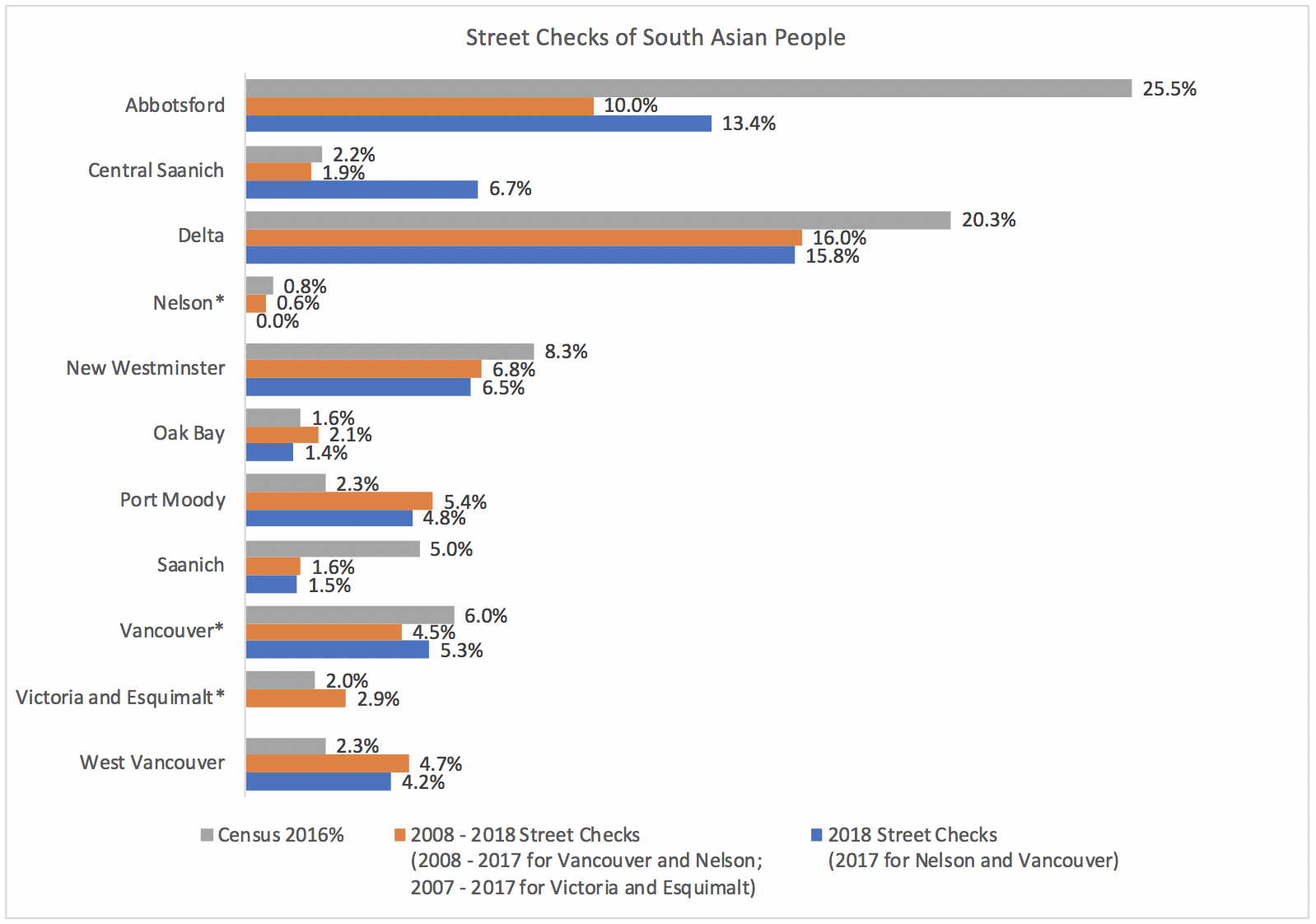

The data also show a number of police departments disproportionately targeting Hispanic people, Middle Eastern and South Asian people. Numbers for all municipal police departments are below.

Street checks where ethnicity was recorded as “Blank” or “Unknown” were excluded from totals when calculating percentages.

When Vancouver PD released supplementary street check data under FOI in July 2018, breaking their street checks down by gender and ethnicity, it showed the department disproportionately street checks Indigenous women. The same is true of B.C.’s other municipal police departments. For example, 0.6% of women in West Vancouver are Indigenous, but 15% of women street checked by the West Vancouver Police Department between 2008 and 2018 were Indigenous; in 2018, that number was 17.6%. That year, Indigenous women were 30.7 times more likely to be street checked in West Vancouver than white women.

VicPD and Delta PD did not provide street check data broken down by gender and ethnicity.

If you’re a white dude twitter troll or a police department flack looking for those hot hot “what about white people” stats, white people aren’t stopped, questioned, arrested and killed by the police because they’re white. The full data set is at the bottom of the post; best of luck with your tweets and/or press release about the importance and impartiality of street checks.

Street checks and poverty

The systemic racism upheld through street checks also intersects with policing poverty.

In a 2014 survey, SOLID asked people without fixed addresses questions about police, and a total of 45 per cent of respondents “disagreed completely” with the idea that “Victoria Police respond in a fair way when dealing with racial, religious and ethnic communities of this area.” Only 5 per cent of people living in Victoria and Esquimalt, Lkwungen territories, are Indigenous, while 33 per cent of the individuals living in homelessness identify as Indigenous or having Indigenous ancestry. People living in homelessness and poverty, and particularly Indigenous people and people of colour, are frequently targeted by police, including for street checks.

Excerpt from 2012 VIPIRG report, Out of Sight: Policing Poverty in Victoria, documenting VicPD racism. Text says: “Notes from the field: ‘I’ve been treated unequally because my name identifies me as Métis. Police don’t like the homeless because we’re a disease. But we take care of the city because that’s where we live.’ ‘When I was homeless, I’d be walking along. And they’d leave me alone but would really be hassling the First Nations person.”

Stanley Q. Woodvine analyzed Vancouver PD street check data in 2018, writing for the Georgia Straight that “being homeless in Vancouver has generally meant being a target for police street checks. … [H]omeless people—and the simple act of them being homeless—pushes all the wrong buttons, so far as law enforcement is concerned.”

Charter violations and “Moratoriums”

Nova Scotia brought in a “moratorium” on street checks earlier this year, which the province changed to a “ban” in October 2019. But the moratorium was never really a moratorium. Like the previous policy, it still allowed subjective stops for “suspicious” activity. And the ban isn’t really a ban. Black people reported that street checks continued during the alleged “moratorium” and were likely going to continue during the new “ban”; they just wouldn’t be called “street checks.” On the initial Nova Scotia “moratorium,” Desmond Cole said:

“The province recently announced a temporary moratorium, the police will not be allowed to stop people solely based on their race. Of course the Charter of Rights and Freedoms already tells the police that they cannot stop me based on the colour of my skin. So to announce that you’re not going to do that anymore is to admit that that’s what you’ve been doing the whole time.”

B.C. is bringing new standards for police stops into effect on January 15, 2020. Those standards say that municipal police boards must ensure that there are written policies stating that the “Decision to stop must not be based on identity factors alone”; that “random or arbitrary stops [are] not permitted … unless authorized by law or case law”; and that “officers are not permitted to request or demand, collect, or record a person’s identifying information without a justifiable reason.” That includes: “reasonable grounds to believe that an offence has occurred or is about to occur” or if “the officer reasonably believes the interaction … serves a specific public safety purpose.” They can also request information when responding to calls for service.

Wherever police exist and officers are allowed to subjectively stop and question people — whether those stops are called street checks, whether they’re on the books or off the books, and whether or not officers need to explain how those street checks were “justifiable” — racist police stops and police violence against Indigenous and Black people will continue. Focusing on individual bias, or street checks for that matter, won’t correct for the fact that racism is a foundational element of policing in Canada, built into the system itself.

VicPD calls its racism problem a data problem

Of the 11 municipal police departments, only VicPD initially refused to provide any information. They finally released some data after multiple FOIs, including one that showed they had put together the information to respond to the initial request, but decided to withhold it. Twice. A third FOI for the exact spreadsheet they were emailing around was successful.

When VicPD finally released their street check data, they also sent a lengthy cover letter. VicPD’s database was a mess, they said, so who could really say how many people were street checked, what their ethnicity was, or if the department’s racist street checks were even street checks? After trying and failing to withhold information showing that VicPD disproportionately street checks Indigenous and Black people, they were awfully quick to suggest it was actually a data problem.

VicPD said its data included things that shouldn’t have been called street checks; that people were included in street check reports who weren’t the subject of a street check; that the department’s “ethnicity data … is not likely to have a high rate of accuracy”; and that they couldn’t provide gender and ethnicity data for street checks without reviewing each individual file. On all of these points, it’s worth noting that VicPD uses the same database as the other municipal police departments, which all disclosed street check data upon request.

VicPD also said the department had reviewed all of its 2017 street checks and would publish a report with improved data, as well as information on what is and isn’t a street check. At the risk of spoiling what’s sure to be hot garbage: if that report ever sees the light of day, it’s going to be hot garbage. Other jurisdictions including Edmonton and Vancouver have gone to great lengths to say their racist street checks weren’t really racist and/or weren’t really street checks, or that their street checks were correlated with people they were actively policing and labeling “criminals.” VicPD’s response suggests they’ve embraced the same narrative.

As an example of the sleight of hand VicPD is likely going to try, their street check reports show that the department often categorized “curfew checks” as street checks. During a curfew check, officers work to recriminalize people by visiting their homes to follow up on parole conditions. A review of one month of street check reports from July 2017 suggests VicPD officers disproportionately check Indigenous people for “curfew” (34 per cent of the 29 curfew checks in July 2017). VicPD would likely say that it’s unfair to call those examples racist street checks, when they were actually racist curfew checks, the result of policing and judicial systems that disproportionately incarcerate Indigenous people and work to revoke their parole.

The Victoria and Esquimalt police board quietly announced in March 2019 that they have been looking at street check protocols and “how those might be reframed and reconsidered,” but no recommendations have been released. At the September 2019 police board meeting, the “legal hub” of VicPD said that they advise the department on “behaviours to adopt” to minimize public complaints, including how to street check people “legally but effectively.”

VicPD’s broad street check policies have allowed officers to stop and question people “at the officer’s discretion” for years, engaging in discriminatory detention and information gathering. Instead of VicPD acknowledging that street checks might be a problem, they tinkered with their database and coached officers on how to keep street checking people in perpetuity.

An Indigenous woman discusses her son’s experience with Greater Victoria police. Excerpt from the 2018 Michael Regis report, “Policing in Greater Victoria: A Study in Addressing the Gaps in Engaging Greater Victoria's Diverse Communities.” Text says: “One participant mentioned that her son is regularly targeted and stopped by the Greater Victoria Police even though he is not involved in crime. Her son is scared to leave his home because he hates being pulled over so frequently. He is a construction worker and is regularly stopped as he is walking home from work, even though he has his construction tool belt and work clothes on. She stated that officers are rude to her son and do not offer him a rational reason for being stopped. In another experience, her son was stopped by officers after buying a drink at a corner store. An officer grabbed his drink without asking and smelled it to see if there was alcohol in it.”

Conclusion

Black and Indigenous people have been calling out the harms of street checks across the country for years, in Toronto, Halifax, Edmonton, Lethbridge, Saskatoon, Montreal and elsewhere. Earlier this year, the Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre recommended “End[ing] the policing practice of street checks,” and Pivot Legal published a memo calling street checks an “illegal and racist practice.”

El Jones, writing about street checks in Nova Scotia, said “it is a mistake to treat street checks as a single issue detached from broader issues of state violence.” Whatever communications materials B.C.’s municipal police departments might cook up, street checks are just one example of the systemic racism that policing and the criminal justice system uphold every day in B.C. and Canada. Those systems disproportionately kill and incarcerate Indigenous and Black people. Street checks, so long as they exist and in whatever form they exist, can never be separated from that context.

Documents for download

Excel spreadsheet with worksheets for: Total street checks; % of population street checked; street checks by ethnicity; overrepresentation in street checks; street checks of Indigenous people; street checks of Black people; street checks of Hispanic people; street checks of Middle Eastern people; street checks of South Asian people; street checks by ethnicity and gender; street checks of Indigenous women; likelihood of street check; and “reason” for street checks: DOWNLOAD

Excel spreadsheets for individual municipal police department data as released through FOI or as transcribed from hard copies. Spreadsheets may include additional data such as zone information: DOWNLOAD

Copies of the original records as released through FOI, including scans of hard copies: DOWNLOAD

Excel spreadsheet showing the calculations to convert Census 2016 data to match police departments’ street check ethnicity categories: DOWNLOAD