136 people are peeing in Victoria right now

Building on some Internet math, Statistics Canada data, and an average pee time of 21 seconds and 6.5 pees per day, about 136 people are peeing in Victoria at any given time. At 231 mL a pee, that works out to 1.5 litres pps (pee per second) flowing from the local population.

Victoria’s daily urine output, 128,688 litres, presented as a yellow milk jug infographic.

These numbers don’t account for things like commuters and regular sleeping hours, but any way you add it up it’s a lot of people who need to pee, which is one of the reasons why it’s sad that Victoria lost a low-barrier washroom in April when the Atrium locked its bathroom doors.

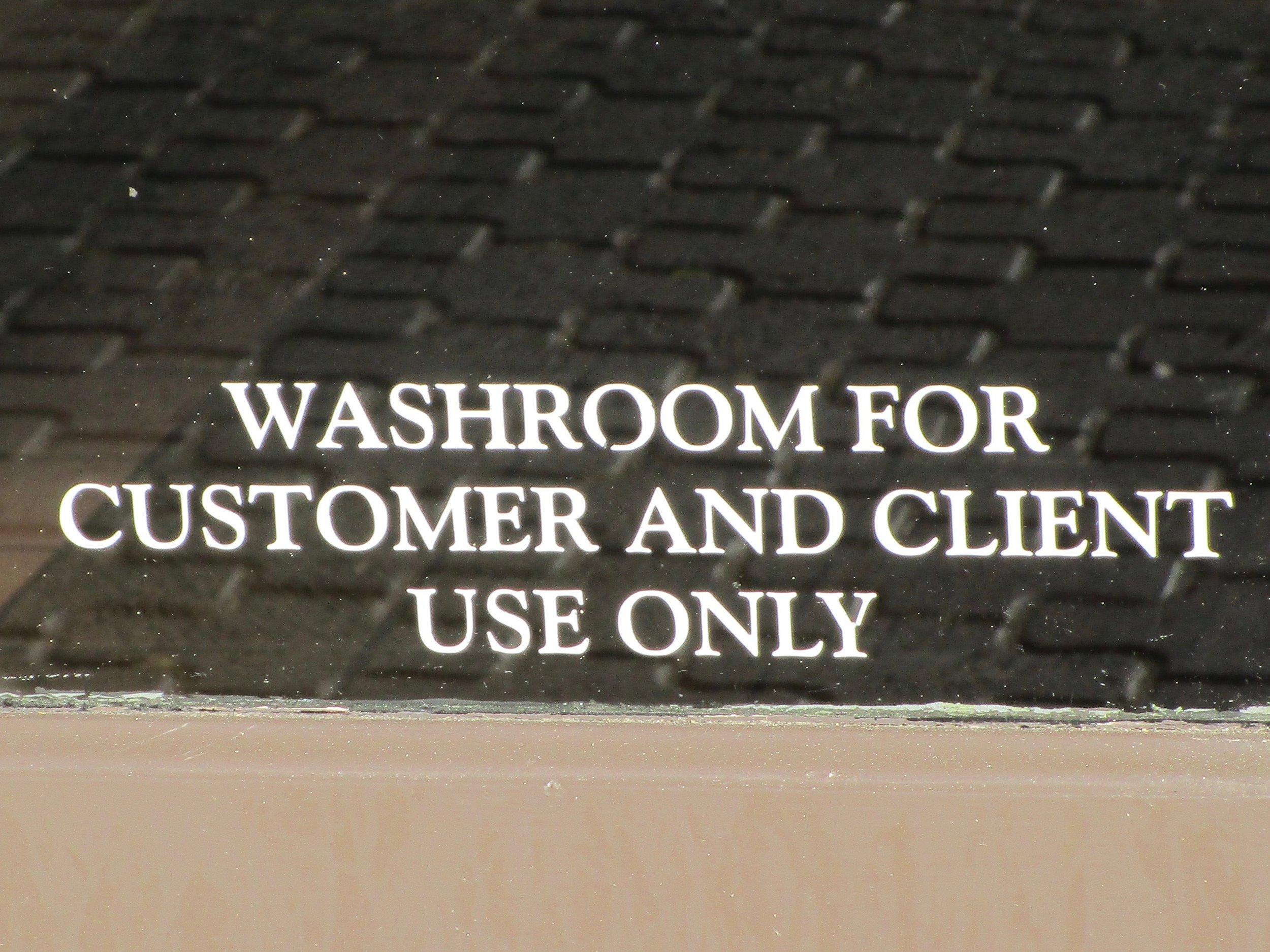

The Atrium building, at Yates and Blanshard, has an open indoor area that creates an illusion of public space. That space used to include gender neutral washrooms that you could access without always encountering someone who might police your presence. Unfortunately, in April the Atrium put up signs saying its facilities are for customers only. Before using the bathroom, you now have to ask permission from security first, or from staff in the coffee shop.

The doors to access the washrooms in the Atrium building were locked in April 2018.

Policing the use of private bathrooms and limiting the number of public washrooms are strategies used to control people who may have limited access to washrooms or private space. Victoria city councillors, for example, have used a lack of washrooms to ban people from sleeping in certain parks. The fact that people may seek out a washroom as a semi-private space to use drugs is also used as an excuse to limit the number of washrooms, hire security, and lock bathroom doors.

Public washrooms by the numbers

While most people have ready access to private washrooms in their home or workplace, public washrooms are often closed at night, have limited facilities, and may include a permanent security guard.

The Times Colonist published a list of “public” washrooms in 2014 that included privately-owned spaces, such as the Bay Centre. Officially, however, the city claims 22 public washrooms, almost exclusively in city parks:

A map of the City of Victoria’s public washrooms. Excludes washrooms not managed by the city, such as the public library.

Maybe 22 sounds like a lot, but the washrooms are scattered across the city, and they’re not always available. Only three are open 24/7:

The Langley Street single-stall washroom;

Centennial Square’s washrooms (featuring 24/7 security and a “5 minute max” sign); and

The Pandora Street urinal.

Some of the washrooms are small, locked (Johnson Street Parkade), or lack amenities necessary to wash up or get organized, for anyone who might want to do so. Only a few public washrooms offer soap, and even fewer have a mirror. And the northern Ross Bay Cemetery washroom either doesn’t exist or is exceptionally poorly advertised.

A City of Victoria public washroom.

The City reports it has three washrooms with “extended” hours, one of which becomes port-a-potties overnight. The extended hours program began in 2015 in response to sheltering in parks and came with “security services … to assist with smooth operations” and “any minor situations that may arise,” which I’m guessing doesn’t mean unclogging toilets.

The remaining 15 washrooms are only open “after dawn and before dusk,” which is ridiculous. Some of my best peeing happens after dusk! The city’s limited hours have everything to do with budgeting choices and controlling access, and nothing to do with the reality of people’s needs.

The City of Victoria’s 22 official public washrooms, by hours of operation. Excludes washrooms not managed by the city, such as the public library.

A friend also pointed out that the Atrium had been one of the few downtown gender neutral washrooms, a single-stall unicorn in terms of facilities easily accessed by the public. Out of the City’s 22 public washrooms, I believe only the Langley Street single-stall washroom is entirely gender neutral (I couldn’t find the second Ross Bay facility to check), and the Inner Harbour washrooms also have one gender neutral bathroom. Anyone who’s looking to the city to provide gender neutral washrooms is mostly out of luck.

Additionally, a recent report by the Victoria Disability Resource Centre on some of the city’s washrooms found that “a lot of them failed to meet various standards” for accessibility. That includes the Langley Street washroom, which was described as “fully accessible” by the city when it was named “Canada’s Best Restroom” in 2012.

Depending on your needs and where you are, the city’s public washrooms may not be a viable option, which is a big problem for such an important amenity.

Private washrooms for some; locked doors for others

Washroom politics plays out in both “public” and private spaces, limiting who can use downtown Victoria and how.

There are lots of private washrooms scattered about, but many of them come with the same warning as the Atrium: you can only use them if you pay up. Even for institutions that aren’t actually policing those rules, the message is still there, and will stop some people from requesting access. Some of these washrooms may not be options for people who are perceived as poor, people who are socially anxious, and so on.

When I mapped downtown signs in September 2017, I counted 26 parcels that had a “No Public Washroom” sign somewhere on the property, telling people to forget about it before they even opened the door:

Parcels in downtown Victoria with “No Public Washroom” signs in September 2017. Parcels may contain more than one business, some of which may have had no signs posted.

Given how certain ‘rules’ (such as “no trespassing”) are selectively enforced based on how people are perceived, I’m sure some of these signs are flexible. If you’ve got a full card in privilege bingo, then you can probably use Market Square’s washrooms without buying a waffle first. As noted above, some of Victoria’s public washrooms also have rules about when they can be used, how long they can be used for, and under what level of surveillance, which will also change based on how people perceive you.

No washrooms? No camping

It’s not just relieving bodily functions or washing up that’s at stake with Victoria’s limited washrooms; it’s affecting people’s ability to shelter, too. According to Mayor Helps, part of the reason for banning camping in four small Victoria parks in 2016 was that they had no washrooms. And earlier this year, then-Councillor Margaret Lucas used the same argument when she successfully asked council to ban overnight campers from Reeson and Quadra parks:

I understand … that shelter mats are not a home, but neither is camping in a park. Especially these two parks, where there are no washroom facilities. … They’re very small parks. We’re not talking about very large parks with washroom facilities. These are, as you know, two very, very small parks, without any facilities whatsoever. At least in the shelter spaces they do have washroom facilities, and they have warmth. … Being on a shelter mat seems to me a heck of a lot better than being out in the pouring rain in a tent with no washroom facilities.”

At no point during the great “washroom facilities” speech of February 2018 did Councillor Lucas suggest adding washroom facilities in either park. That seems like a strange omission for an avowed washroom lover, but her apparent love of toilets isn’t supported by the rest of her report to council. In that report, Councillor Lucas said she talked to nearby residents, businesses, and the police before suggesting a camping ban. As for anybody sheltering in the two parks, who would be affected the most… If she talked to them at all, she didn’t think it was worth mentioning in her report. Talking to people could have led to all sorts of uncomfortable requests, of course, for things such as permanent housing, maybe, or — heaven forbid — washrooms.

Cara Chellew, author of #defensiveTO, says the absence of things such as washrooms or benches is “a form of defensive urban design” meant to discourage “groups of ‘undesirable’ people.” Victoria’s city council has control over whether or not there are washrooms in city parks, and in the past mayor and council have shown they are willing to use that power to deny people a space to shelter to discourage their use of public space.

Washrooms and drugs, oh my

One of the reasons businesses and city council may be so washroom shy is the fact that when other options either aren’t available, close at hand, or otherwise desirable, sometimes people use drugs in bathrooms.

One recent study said “privacy” and a need to find “the closest, easiest location” were two big factors shaping where people use drugs. There is rampant stigma about drug use, and washrooms are a semi-private space where people can avoid being seen. Because people sometimes access washrooms to use drugs, stigma and fear of drug use are used to limit the number of public washrooms, restrict access, and hire security.

Staff and management of local businesses may be reluctant to serve as de facto first responders in the midst of an overdose crisis and may cite that as a reason for locking their bathroom doors, but Victoria doesn’t exactly have a positive history responding to drug use in washrooms. In 2002, Jody Paterson reported that the city was using special washroom lighting to make it harder for people to use drugs. And according to a city report in 2006, the Centennial Square washroom was closed at one point “due to issues with drug use that rendered them unsafe.” In 2009, the income assistance office closed its washrooms “to curb drug use.”

A 2016 report by UVic’s Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (CISUR) reported that “Public injection, including in public washrooms, is more likely when safe facilities and housing are not available for people who inject drugs.” People surveyed by CISUR were increasingly consuming drugs in the washrooms of agencies offering harm reduction or shelter services for a number of reasons, including privacy, a perception of safety, and being away from the public. Since that report was published, Victoria now has multiple overdose prevention sites. However, as long as drugs are criminalized, people are homeless, and nearby spaces or overdose prevention sites aren’t available or desirable, people will continue to access washrooms to use drugs. Stigma also contributes to people seeking these semi-private spaces, while locking formerly public washroom doors reminds people that that stigma exists.

Conclusion

Restricting washroom access shapes how people move through the city, and city council knows it. In the past, the city has gone out of its way to accommodate late-night bargoers’ washroom needs — with pop-up washrooms or urinals, for example — to influence where they peed in the downtown core.

At the same time, the city has also closed public washrooms “due to issues with drug use”; begrudgingly extended three washrooms’ hours, with security; limited its central washroom to “5 minutes” only; and banned people from camping in parks because the city chose not to provide washrooms.

Public washrooms are a necessity, and in the current climate of criminalization and stigma, washrooms also offer a convenient, semi-private place to use drugs. Whether you’re the Atrium or the city, locking bathrooms is a way to control certain people by denying them access to an essential service. As Cara Chellew writes, when washrooms aren’t there, these “ghost amenities … mak[e] the city more hostile for everyone who is in need of rest and relief.”

Having plenty of open and accessible public washrooms, while working to address homelessness and the stigma and criminalization of drug use, would ensure that people can access washrooms when they need them, for any reason. Including the 136 people peeing right now.