“Contact with a police vehicle”

On December 21, 2018, VicPD put out a press release with the headline “Witnesses sought after assault with a weapon.” VicPD said they had arrested someone for an alleged assault, who, “During the course of the arrest … came into contact with a police vehicle” and went to the hospital.

VicPD’s own records show that despite their headline, VicPD didn’t issue the press release to investigate the initial alleged assault. It was part of an investigation into their own officer, who drove into a young person with enough force to destroy “a brick and mortar planter approximately three feet tall.”

VicPD’s press release hid what actually happened from the public, and the events that followed demonstrate the limitations of police investigating police, and the lack of accountability for daily assaults by VicPD officers.

Anatomy of a press release

Police communications departments, including VicPD, work to shape a narrative that absolves officers of complicity in potential wrongdoing. It wasn’t in VicPD’s interest to disclose how someone “came into contact with a police vehicle,” but VicPD records, obtained through FOI, provide some detail.

On December 15, 2018, at 12:25 am, VicPD received a 911 call from Douglas and View about an apparent pepper spray incident. Sgt. Darrell Fairburn responded and detained a group of people, before radioing to say that one person was running away.

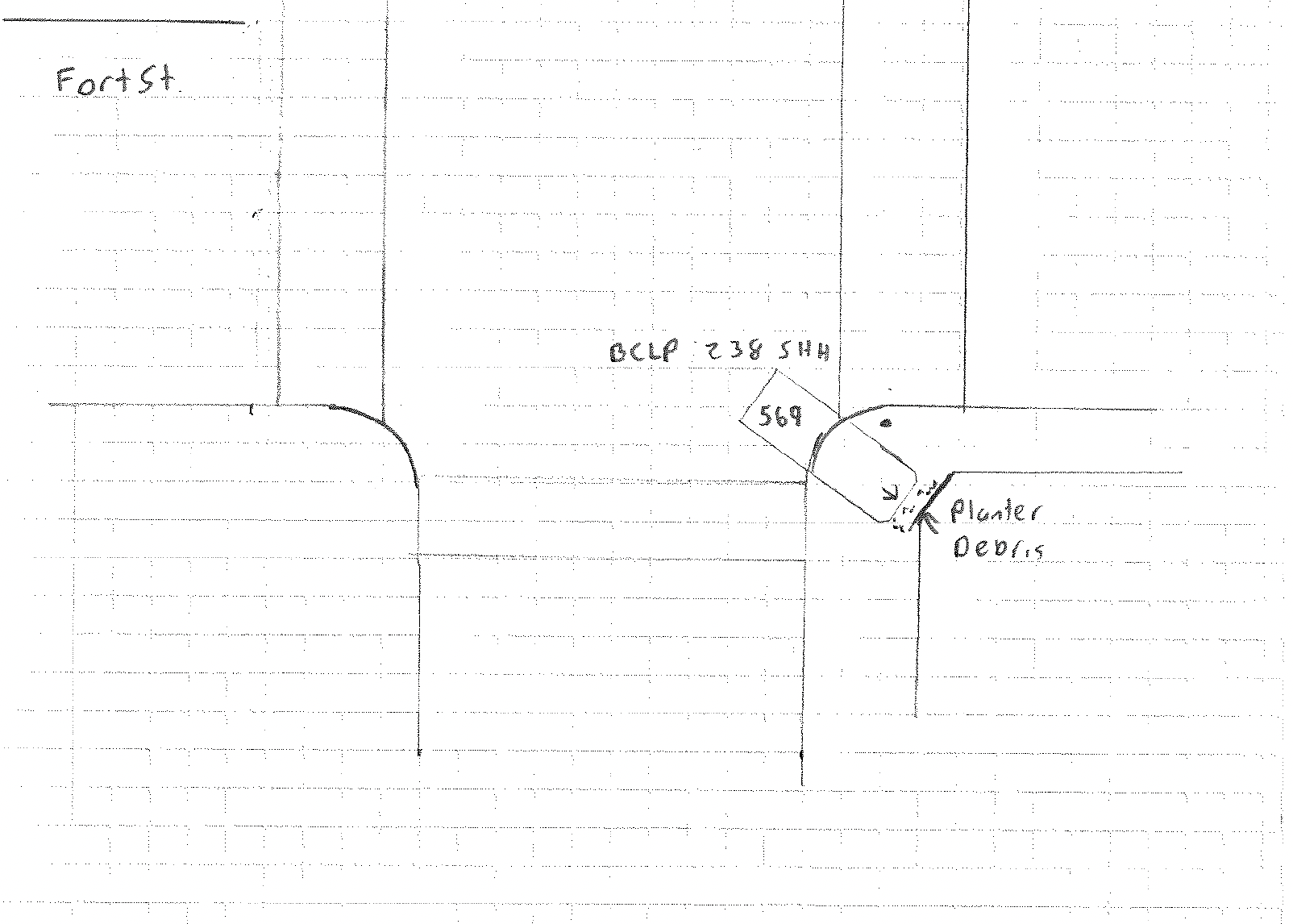

In response, an officer whose name VicPD withheld (assigned that night to unit D81, see note*) went the wrong way down Government Street and drove into someone he thought was the person Sgt. Fairburn was talking about.

Witnesses said D81 was driving at an “average,” “slow” or “medium” speed, with lights but no siren, and said “stop” over his PA system before he “steered diagonally into the male” at the corner of Government and Fort, in front of what was then Birks Jewelry. While key passages are redacted, it is clear D81 ultimately hit the person and destroyed a brick planter. According to one witness, “The bricks all fell down and the male fell down to the ground when they fell.”

VicPD usually doesn’t hesitate to run stories on downtown assaults to try to associate policing with community safety, but when their officer was implicated, it was six days before they said anything. They did so only because the officer investigating D81’s actions was looking for witness cellphone video. But VicPD’s communications team transformed this request into a statement focused on the earlier alleged assault, without mentioning they were looking for video of D81.

Notes from Sgt. Robson showing he requested the press release to look for cell phone video related to D81.

VicPD’s press release also didn’t mention that within 19 minutes of the initial 911 call, they believed the person D81 hit wasn’t the person who committed the alleged pepper spray assault. While the person D81 hit was the same person who had run from Sgt. Fairburn, Sgt. Fairburn identified someone else as the primary suspect shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, VicPD called the person D81 hit a “suspect” in their press release. The label of “suspect” is useful framing for VicPD to support a narrative that its violent response was somehow in the public interest.

Excerpt from Sgt. Robson’s summary of radio transmissions indicating someone other than the person D81 hit was the primary suspect.

When the Times Colonist ran a story about the incident based on VicPD’s press release, any mention of a police car or “contact with a police vehicle” was gone. “Victoria police are looking for witnesses to an assault with a weapon last weekend,” the Times Colonist said, for an incident that occurred at Douglas and View — not for video of an officer hitting someone with his car at Government and Fort.

VicPD’s press release obscured the fact that they were investigating their officer, that he had hit someone with his vehicle, and that they were ostensibly looking for cell phone video of him doing so. Not surprisingly, ten days later, the investigating officer said “No witnesses have come forward” with the video evidence VicPD never publicly asked for. He issued his concluding remarks and said the matter could now be forwarded for outside review.

VicPD’s radio transmissions from that night (subtitles available). VicPD withheld some of D81’s broadcasts.

Police investigating police

Sgt. Shawn Robson began the concluding remarks for his investigation into D81 by citing a partial Criminal Code definition of “assault” as “applying force intentionally to that other person.” Not mentioned is that assault also includes “attempt[ing] or threaten[ing], by an act or a gesture, to apply force to another person.…”

D81’s actions appear to meet the definition of assault with a weapon, but Sgt. Robson’s focus on whether someone “intentionally” applied force may suggest he wrote a narrative that D81 didn’t mean to hit anyone. We don’t know, because everything following the definitions Robson cited is redacted, and VicPD withheld relevant statements from witnesses and D81 about D81’s actions.

Excerpt from Sgt. Robson’s concluding remarks. The report is one page long. Everything that follows what is included in this image is also redacted.

In the Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner’s (OPCC’s) annual report in 2020, the OPCC gave its account of what happened. The OPCC said D81 had tried to block the individual with his car and left a small gap between the planter and his car. “When the male attempted to squeeze between the planter box and the police vehicle’s front bumper, [D81] released the police vehicle’s brake slightly and trapped the male between the police vehicle's bumper and the planter box.” The OPCC said this occurred “at low speed” for “one to three seconds.”

VicPD withheld all key passages in its records about when D81 actually hit the individual, as well as D81’s account of his actions. It is impossible to say what witnesses saw at that exact moment, what D81 says he did, and whether their statements support the OPCC’s conclusions. What is clear is that D81 hit a young person with enough force to send him to the hospital.

Excerpt of one witness’s account, as recorded by VicPD. VicPD redacted passages discussing when D81 hit the young person.

Hitting someone with your car carries an incredibly high risk of injury. When a judge commented this year on an individual who intentionally drove into a VicPD officer, the Times Colonist paraphrased the judge as saying “using a car as a weapon on a person who could not escape … is an extremely serious offence.” By the OPCC’s official narrative, D81 “trapped” the young person with his car.

We do know what consequences D81 faced, such as they were. For “using a police vehicle to apprehend a suspect,” the OPCC said D81 committed misconduct. The OPCC agreed with VicPD senior management’s recommendation that D81 should receive a written reprimand and training on “operating police vehicles and the application of a police vehicle as a force option.”

OPCC findings from its 2020 annual report.

The aftermath of this incident is a testament to the lack of accountability when police investigate police. VicPD investigated their own officer; they issued a press release that may have hampered a meaningful search for evidence; and, for hitting a person with a police car to make an arrest, they recommended a written reprimand and training. The OPCC agreed that was punishment enough, and it took two years for their limited narrative of what happened to be made public.

Unless they are criminally charged, there is no mechanism to publicly name officers who have committed misconduct in British Columbia. D81 would have been free to continue serving as a VicPD officer, with no public account linking him to his actions.

Police use of force

On the day you are reading this, VicPD will commit an average of one assault with a weapon, through threats or physical violence.

When VicPD kills someone — John Seguin, Rhett Mutch, Lisa Rauch, and others — there may, a year or more later, be a public coroner’s report and/or Independent Investigations Office report summarizing VicPD’s actions. Both reports routinely absolve officers of wrongdoing.

But when it comes to the day-to-day violence perpetrated by VicPD, there is rarely a public account. In 2020, VicPD used weapons on people at least 59 times, and used weapons to threaten people at least 303 more times. VicPD is required to disclose those assaults, and the provincial government summarizes each year’s police violence statistics the following fall.

VicPD fails to meet that minimum standard of public disclosure for its other assaults. Asked for data on VicPD’s use of “physical control hard” (punching and kicking people) and “lateral neck restraints,” VicPD first said the information was available online, which is false. Pressed to provide the data, VicPD simply stopped responding. When Vancouver PD responded to the same FOI for their own department, the figures were as troubling as one might expect.

In the absence of eyewitness accounts and reporting, it takes lengthy work to get information on any police assault, and it is in VicPD’s interest to withhold those records. After learning about this incident from the 2020 OPCC annual report, I filed an FOI for any incident and arrest reports and related video or audio. VicPD initially refused to release anything, arguing it was all personal information.

VicPD initially refused to disclose any records.

After an informal complaint, VicPD released written records. Then, 364 days after my initial FOI, and following a formal complaint with the Information and Privacy Commissioner, VicPD released surveillance video and radio transmissions from that night.

Given VicPD’s resistance to disclosing any records, and in particular audio and video, it is remarkable how little the surveillance video shows. There are flashing lights from D81’s car off camera, and later, an officer puts up police tape. Much like with its press releases, VicPD felt it could pick and choose what information to release, and they ignored information disclosure laws until forced to do otherwise.

This video (no audio) adds little, but it is testament to the fact that you can get video from VicPD through FOI. VicPD withheld 21 minutes, ostensibly when people were walking by.

In the 364 days it took to get details on this incident, VicPD committed approximately 364 assaults with weapons, through threats and physical violence. Details of the majority of those assaults will never be made public. The fraction that trickle through will mostly be told through police press releases, which tell the public that the assaults were committed in the name of safety, and were the only possible outcome.

The records for this one incident where VicPD said someone “came into contact with a police vehicle” show how police press releases can mask police violence. It is a choice to let police departments hide the details of their daily assaults. And more importantly, it is a choice to let police violence continue.

*Note: D81 is not a badge number. If you see anything linking D81 to a specific officer, it does not mean it was the same officer assigned to D81 on December 15, 2018. I concluded the officer assigned to D81 that night hit this individual due to: a radio transmission at 12:26 am saying 71 and 81 were called to respond, which is summarized in the written records as “D71 and [redacted] to respond”; and a radio transmission at 12:34 am mentioning 81. If anyone has reason to believe it was not the officer assigned to D81 on December 15, 2018 who hit the individual, I am happy to correct this post.