“They could have killed the man”: Police cars as weapons

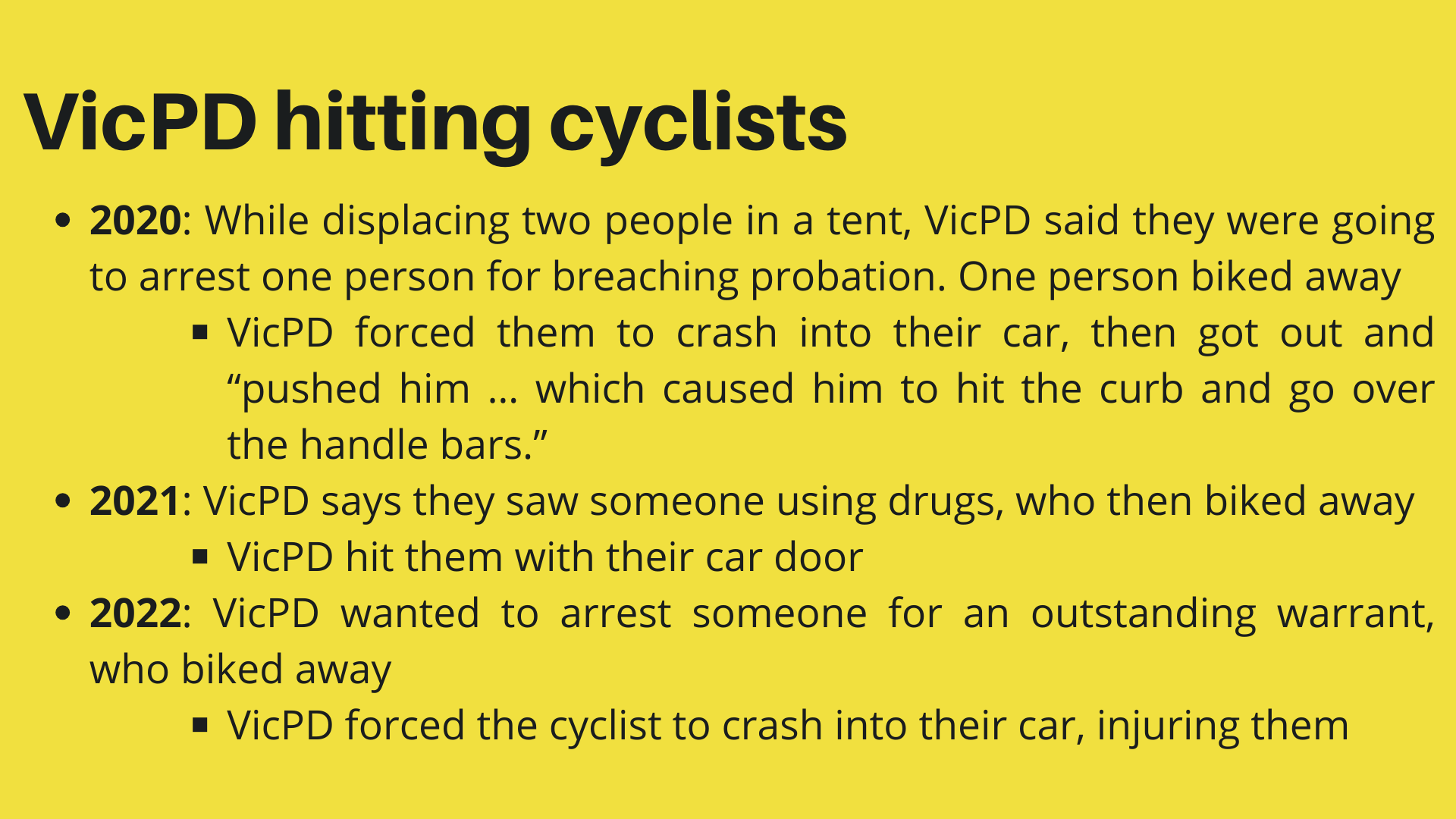

In 2017, after a VicPD officer saw a cyclist without a helmet, they “drove recklessly” after them. The officer cut them off with “a sharp and sudden turn into [their] path,” forcing the cyclist — who the officer said they initially wanted to stop for a helmet violation — to crash into their police car and fall off their bike.

VicPD now says that using a police car “as a use of force carries risk and potential serious harm to individuals, and should only be reserved … to prevent death or serious bodily harm.”

Despite that policy, FOI records show VicPD still has a low threshold for hitting people. Since January 2018, VicPD officers have intentionally hit at least nine people using their police cars or car doors, including people on foot, bikes, and a scooter.

Based on the officers’ notes, none of these cases appear to have stopped anyone from being killed or seriously harmed. On the contrary, by using their cars as weapons, VicPD injured multiple people.

At least nine incidents

The Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner (OPCC) has upheld at least three findings of misconduct against VicPD officers for hitting cyclists or people on foot. That includes hitting the helmetless cyclist in 2017, failing to stop after hitting a pedestrian in 2015, and pinning someone against a wall in 2018.

To find out how often VicPD uses police cars as weapons, I FOI’d the department’s use of force data. In addition to recording the use of things like tasers and guns, officers reported using “other” types of force.

I filed a follow-up request for reports on VicPD’s “other” uses of force written between January 2018 and November 2023. Those reports revealed that:

At least two officers intentionally drove into someone who was on foot,

At least three officers used their car door to hit a person on foot or a cyclist, and

At least three officers cut off a cyclist or a person on a scooter to force them crash into their car

Screenshot of a VicPD use of force report that says the officer used “Other” types of force. In this case, they used a “police vehicle,” which they said was “effective.”

I also requested two years of VicPD “police motor vehicle collision” reports, which revealed one additional case of VicPD forcing a cyclist to run into their car. Given how often VicPD uses the police collision category (about twice a month), the two-year timeframe for this request was designed to avoid a potential FOI fee.

In total, I found there have been at least nine incidents in the last few years where VicPD admits to using cars or car doors to hit people.

Low threshold for use of force

Despite the high bar VicPD says it has before an officer would intentionally hit someone with a police car, none of the incidents appear to have met that threshold. Instead, they all involved VicPD hitting people who were attempting to leave interactions with the police.

VicPD did not appear to be stopping active violence in any of the nine cases. Instead, their primary reason for hitting people appears to be that they wanted to arrest them then and there.

“Convenience” is not a good reason to hit people with your car.

“They could have killed the man”

VicPD’s use of force reports include the officers’ own statements about what they say they did, but we shouldn’t take their notes as an impartial description of what happened. Fortunately, one of the officers’ reports about hitting a cyclist can be compared against photos and statements posted online by two independent witnesses.

In December 2022, VicPD chased after and hit a cyclist at Douglas and Finlayson. One witness said VicPD could have killed the cyclist and others. Another witness, who has since deactivated their social media account, said VicPD “smoked” the cyclist.

Aftermath of VicPD hitting a cyclist in December 2022. Image source: Twitter.

By the officer’s own account, their decision to pursue the cyclist didn’t appear to have been about preventing death or serious harm. The officer says they saw a person they thought might have had warrants for his arrest. They wrote that they started looking up his name in a police database when he biked away.

The officer says they confirmed there was a warrant for his arrest (read more on VicPD warrant arrests here). The officer then describes a dangerous police pursuit.

Despite choosing to chase after him, they blame the cyclist, saying he “[rode] through parking lots, on the sidewalk, in traffic, in bus lanes, through red lights, etc.” “with little regard for public safety.”

What the officer doesn’t mention is the danger of the pursuit itself. One of the witnesses said the officer was engaging in “very dangerous driving,” including “[through] bike lanes” and in the “opposite direction of traffic.”

While justifying their decision to pursue the cyclist, the officer also wrote that “Based on many previous interactions with individuals with similar criminal history’s [sic]” they thought there was a “high likelihood” he had a weapon.

The officer says they “headed-off” the cyclist, who then “rode into [their] bumper.” The witnesses watching said VicPD “smoked” him, “ran into” and “could have killed [him].”

The officer damaged the man’s bike and injured him, either when they hit him with their car, pinned him to the ground, “pushed” him into the hood of their car, or a combination of the three.

Based on the descriptions provided by both witnesses and VicPD, instead of preventing death or serious harm, VicPD hurt someone and likely put multiple people at risk during their pursuit.

They didn’t find any weapons.

Taking VicPD to court

The events described above — cutting off a cyclist to force them to crash in 2022 — match the 2017 incident where an officer cut off the cyclist who wasn’t wearing a helmet. It appears to be a common technique for VicPD.

In 2020, while displacing two men sheltering in a tent, VicPD told one man they were going to arrest him for breaching probation and a no contact order. When one of the men cycled off, VicPD forced him to crash into their car. He didn’t fall off, so the officer got out and “pushed him … which caused him to hit the curb and go over the handle bars.”

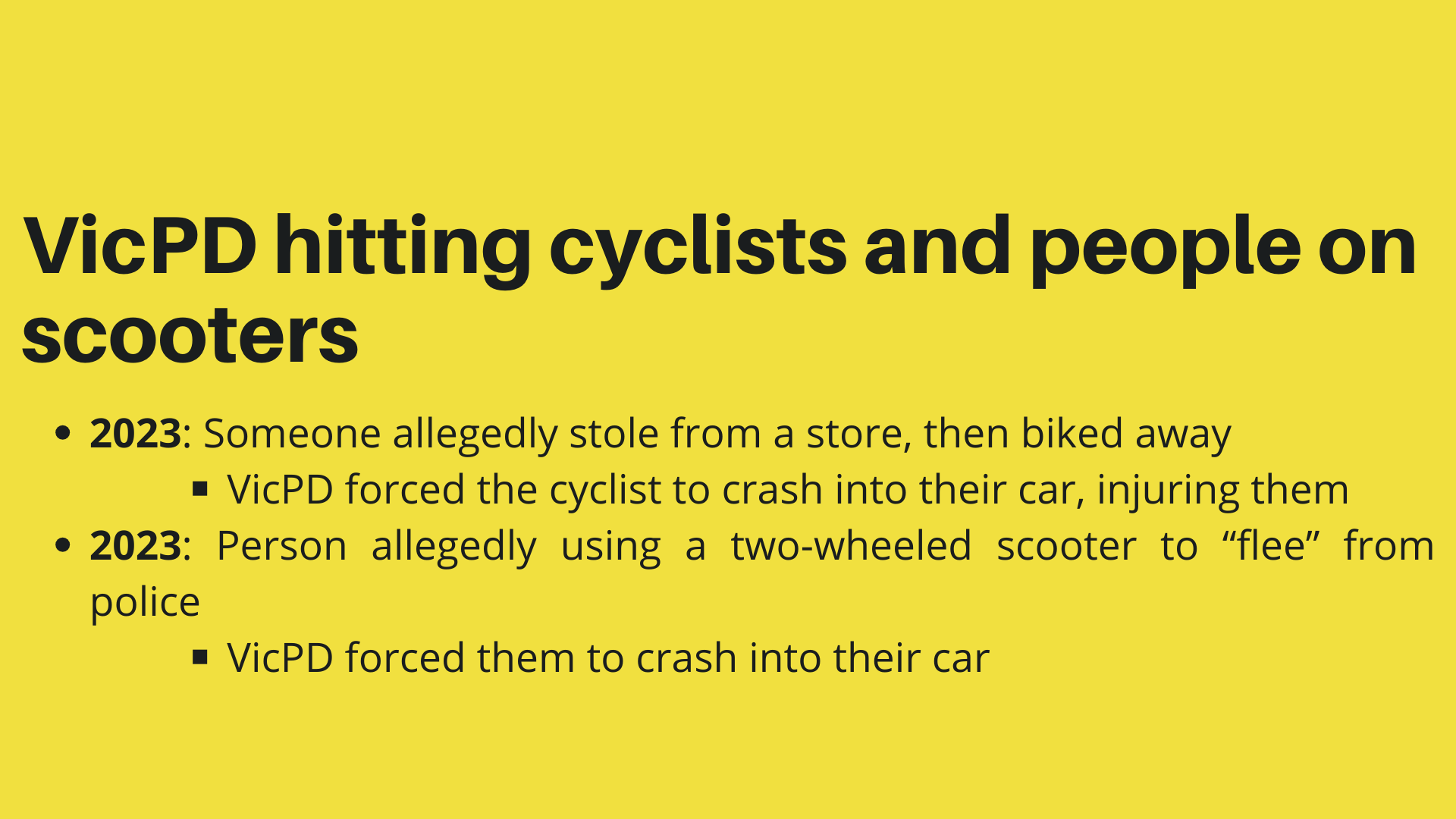

VicPD used similar techniques twice in 2023, once to force someone on a two-wheeled scooter to crash into the side of their parked car, and once to cut off a cyclist who allegedly stole from a consignment store.

In addition to these incidents — and not included in FOI records released by VicPD — another cyclist is currently taking VicPD to court. He says an officer hit him with their car in 2023 and put him in hospital.

The complainant says he biked through a red light at 10:30 pm, and an officer turned on their lights and sirens. He says he thought the officer was going to drive past him, but instead, after less than a block, he says the officer “drove beside [him] and hit [him] with her vehicle,” “knocking [him] to the ground.”

He says he was rushed to hospital and had a dislocated shoulder, and that VicPD seized his bike, which he says they damaged. He is suing VicPD for $16,500 for the cost of the bike, two weeks of lost wages, and pain and suffering.

Statement of Claim from 2023 where a cyclist alleges a VicPD officer hit him with their car. Source: Court Services Online.

In their response, VicPD appears to deny the allegations, deny that he was injured, and say that if he was injured, he should not be entitled to payment.

If VicPD saw a driver go through a red light, and they didn’t immediately stop after VicPD turned on their lights and sirens, would they hit that car and driver after less than a block? Probably not.

But would they hit a cyclist?

Despite VicPD’s denial, the complainant’s description of events is similar to the technique VicPD admits to using in five cases noted above, including the 2017 incident that the OPCC ruled was police misconduct.

[June 2024 update: In an amended court filing, VicPD admitted to intentionally hitting the cyclist]

Conclusion

Finding eight cases of police saying they used a car or car door as a weapon over five years would be alarming. It is troubling that an additional case in two years of police collision reports was not recorded in the same way, suggesting that the use of force data is incomplete.

Additionally, the court allegations for the 2023 incident, which VicPD denies, closely match VicPD’s pattern of behaviour, but don’t appear in either set of records.

Both omissions suggest VicPD is likely hitting cyclists and people on foot more frequently than its “other” use of force reports show.

VicPD says they wouldn’t hit anyone on purpose unless it was to prevent death or serious harm. But the records show that despite multiple reprimands from the OPCC, that simply isn’t true.

According to VicPD, at least three people were injured because of their actions, and the cyclist taking them to court also says he was rushed to hospital.

VicPD’s reports reveal a dangerous pattern of behaviour that they have been warned about, and which shows no sign of stopping.